“What’s going to happen? Tom! What’s going to happen?” Catherine cried out to her husband as she and her children huddled near him. A mob formed outside their house, chanting at Tom: “Enemy! Enemy! Enemy!”

Tom looked to his family and replied, “I don’t know. But remember now, everybody. You are fighting for the truth, and that’s why you’re alone. And that makes you strong. We’re the strongest people in the world. . . .”

Tom’s words trailed off as he turned to stare out the window at the fast-misinapproaching mob. “And the strong must learn to be lonely.”

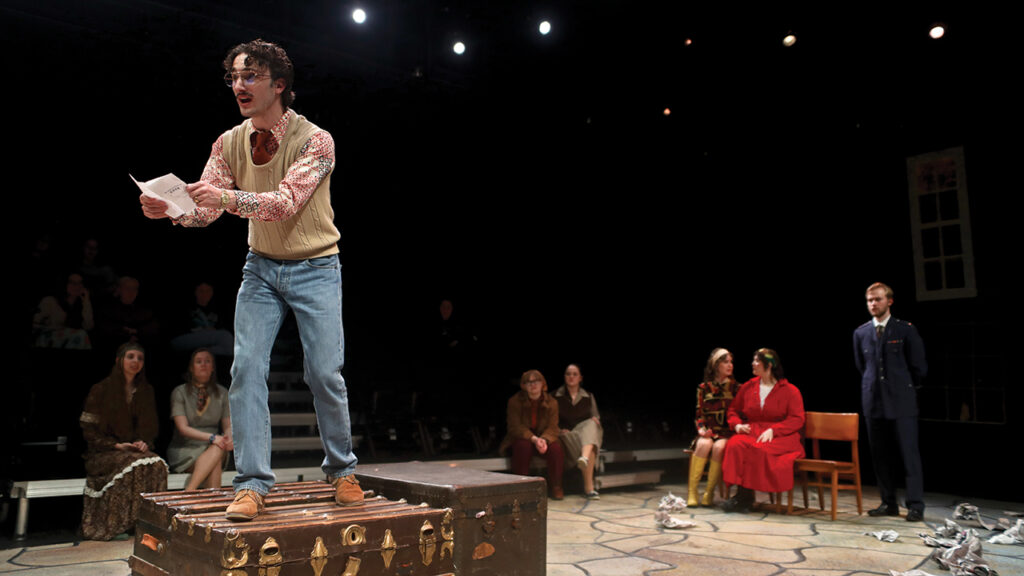

As the mob closes in, their chanting grows louder. A spotlight zeroes in on the family as they stare out the window toward their vengeful neighbors.

Blackout.

Almost every night, as my actors lined up to take their bows, the audience sat quietly, shocked by the precipice on which they had been left, searching for the expected catharsis.

Finally, the applause comes, but after the actors leave the stage, the audience remains seated, their searching unfinished, before slowly filing out of the theater.

This drama, first written by Henrik Ibsen and later adapted by Arthur Miller, centers on a small-town doctor, Tom Stockmann, who discovers that the town’s springs, a major tourist attraction, are being poisoned by a tannery upstream. He alerts the authorities and is met with increasing opposition.

For the authorities of the fictional town of Kirsten Springs, the truth of the poisonous springs and their inevitable poisoning of the town’s people and tourists is not worth the financial loss the town will sustain. As Dr. Stockmann fights for the town to see the truth, he is declared, by his friends and neighbors, to be An Enemy of the People.

Knowing the side the town has chosen, Dr. Stockmann is faced with the question: What is the truth worth? In my director’s statement for this production at Northwestern College, I answered that question, saying that as a Christian my only answer can be a resounding “everything.”

After all, Jesus himself declares, in John 14:6, that “I am the way, the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me” (NIV). For Christians, this is evidence that we should be deeply concerned with knowing and proclaiming the truth.

This summer I read Malcolm Foley’s The Anti-Greed Gospel: Why the Love of Money Is the Root of Racism and How the Church Can Create a New Way Forward. Foley says to resist racism, and all evil, “we have to build communities that relentlessly pry, relentlessly ask questions and relentlessly proclaim the truth about ourselves and those around us.”

Our age of information is, paradoxically, also an age of misinformation. We are fed lies about God’s people and how we should treat them. We are told that some people are more worthy than others, more deserving of love or justice or housing or food or status. The kingdom of God tells us these are lies.

We are told that some people deserve violence and hate and that they deserve less than what we would want for ourselves or our children. The kingdom of God tells us these are lies. To resist these lies, Foley says, “we need an imagination with supernatural lungs.”

Dr. Stockmann and Malcolm Foley both echo Jesus’ call to be beacons of truth. They agree that we must relentlessly fight for the truth, no matter the cost, and that this fight must be waged peacefully.

Peace requires holy creativity. In An Enemy of the People, as Dr. Stockmann is blackmailed and threatened by those he once called friends, he retorts that he will “sharpen his pen like a dagger.” Words, not a sword, will be his weapon.

Once his guests leave and he is alone with his family, he calls them to action. His plan? Not violent insurrection or the silencing of opposition voices. Dr. Stockmann declares he and his family will establish a school to create independent thinkers.

I’m not saying the character of Dr. Stockmann is a perfect example to follow. However, as believers, we must declare with words and actions that the kingdom of God does not respond in the ways of the Empire — the Apostle Paul’s “principalities and powers” of Ephesians 6.

A kingdom response might look more like bringing bread to your neighbor whose political yard sign clashes with yours. Or volunteering at a food pantry where the patrons speak a language other than yours. Perhaps, rather than giving in to the violence of consumerism, which often relies on cheap and unethical working conditions for laborers, you craft a patch for the hole in your jeans.

These actions, however small, declare there is a better way. A way that we need not create on our own, because Jesus showed it to us.

“After all,” Foley states, “the goal of the Christian is not to change or to redeem the world. The role of the Christian is to proclaim with their words and with their life that the world has already been changed.”

Molly Wiebe Faber is an assistant professor of theater at Northwestern College in Orange City, Iowa.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.