Five hundred years ago, on Oct. 31, 1517, German monk and theology professor Martin Luther challenged the Roman Catholic Church by nailing his 95 theses to a church door in Wittenberg. This simple act ignited the Reformation.

The new movement quickly produced two streams of faith: Lutheran, adhering to Luther’s teachings, and Reformed, first led by Ulrich Zwingli, the Luther-inspired pastor of the Grossmunster church in Zurich. Zwingli’s influence on the development of Anabaptism is well documented. Among his followers was a group including Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz, which on Jan. 21, 1525, held the first adult baptisms.

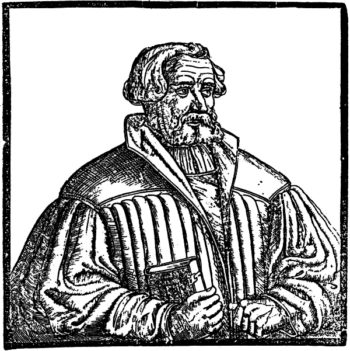

But a straight line can also be drawn from Luther to Menno Simons — a line that runs through Luther’s colleague Andreas Karlstadt. While Luther would become an ardent foe of Anabaptism, even calling for the execution of its adherents, Karlstadt had a tremendous effect on some of its most important leaders.

One 20th-century non-Mennonite historian called him “the intellectual founder of Anabaptism . . . its theological founder par excellence.”

Karlstadt, like Luther, was a theology professor at the University of Wittenberg. (In fact, he had awarded Luther his doctorate in 1512.) And, like Luther, he had growing concerns about the condition of the Catholic Church. The two men became primary shapers of a new “Wittenberg theology,” which was instrumental in driving the Reformation. They were both eventually excommunicated by Pope Leo X.

Many of Karlstadt’s beliefs would become integrated into Anabaptist life and thought. He was an early opponent of swearing oaths — “He who does not honor God will never honor an oath,” Karlstadt said — and downplayed imagery in church.

Aware that many people understood Luther’s emphasis on grace as downplaying works, Karlstadt urged him to give more attention in his preaching to following Jesus in life. He even wrote on Gelassenheit, or yieldedness, which became a key tenet of the Anabaptist faith.

On Christmas Day 1521, Karlstadt conducted the first non-Catholic Lord’s Supper. In contrast to the mass, he wore no vestments but simple secular clothes, did not elevate the bread and the cup and served both to participants. (Only the priest drinks from the cup in Catholic services.) And he did all of it not in Latin but in German, the vernacular of the people.

Karlstadt and Luther didn’t hold identical views on everything, but scholars say there were no serious theological disagreements between the two. Still, by 1522, Karlstadt’s zealousness for reform began putting him at odds with Luther and local civic leaders, who were becoming more cautious about the pace of change. He was marginalized at the university, and in 1523 he moved to Orlamünde, south of Wittenberg, where he became a pastor.

In his new position, Karlstadt began implementing his ideas. He promoted egalitarianism, refusing titles of honor in favor of “Brother Andreas.” He refused to baptize infants.

But Karlstadt was not, by definition, an Anabaptist. He didn’t baptize adults who had been baptized as babies, nor was he rebaptized himself.

Once again, Karlstadt ran afoul of the authorities, who considered his reforms too radical, and he left Orlamünde after only one year. For the next decade, he and his family lived a nomadic life that took them from Switzerland to northern Germany. It also brought Karlstadt face to face with some of Anabaptism’s founders.

In late 1524, Karlstadt and his brother-in-law Gerhard Westerberg met in Zurich with Grebel and Manz and their band of radicals. They raised money to publish some of Karlstadt’s writings, including one on the Lord’s Supper. Westerberg would later become a leader of the Anabaptists at Cologne.

Karlstadt also corresponded with members of the movement in Moravia, and by 1527 he had met Melchior Hoffman, who would become the father of north German and Dutch Anabaptism. In 1529, Karlstadt was in East Friesland working with Hoffman, who was greatly influenced by the former Wittenberg professor, particularly on matters of ecclesiology, worship and the importance of works as well as faith.

Hoffman would proceed to baptize Jan Volckerts, who baptized Jan Matthijs. Matthijs commissioned 12 “apostles” to evangelize the Low Countries, two of whom baptized and ordained Obbe Philips in 1533, who baptized and later ordained Menno Simons.

But the years of transiency took a toll on Karlstadt’s family, so in 1534, he reached a truce with Ulrich Zwingli, the great reformer and anti-Anabaptist of Zurich. That allowed Karlstadt to become professor of Old Testament and rector of the University of Basel, positions he held until he died of the plague on Christmas Eve 1541.

Rich Preheim is a writer and historian from Elkhart, Ind.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.