The editor of a new anthology of Mennonite literary criticism penned over 150 years hopes a carefully curated resource about the past may inform the future of the field. The 736-page book was launched at the Mennonite/s Writing Conference in Winnipeg, Man., in June, a conference that features writers who are Anabaptists by faith and others of Mennonite heritage who are not.

The same is true for the authors featured in In Search of a Mennonite Imagination: Key Texts in Mennonite Literary Criticism (Canadian Mennonite University Press).

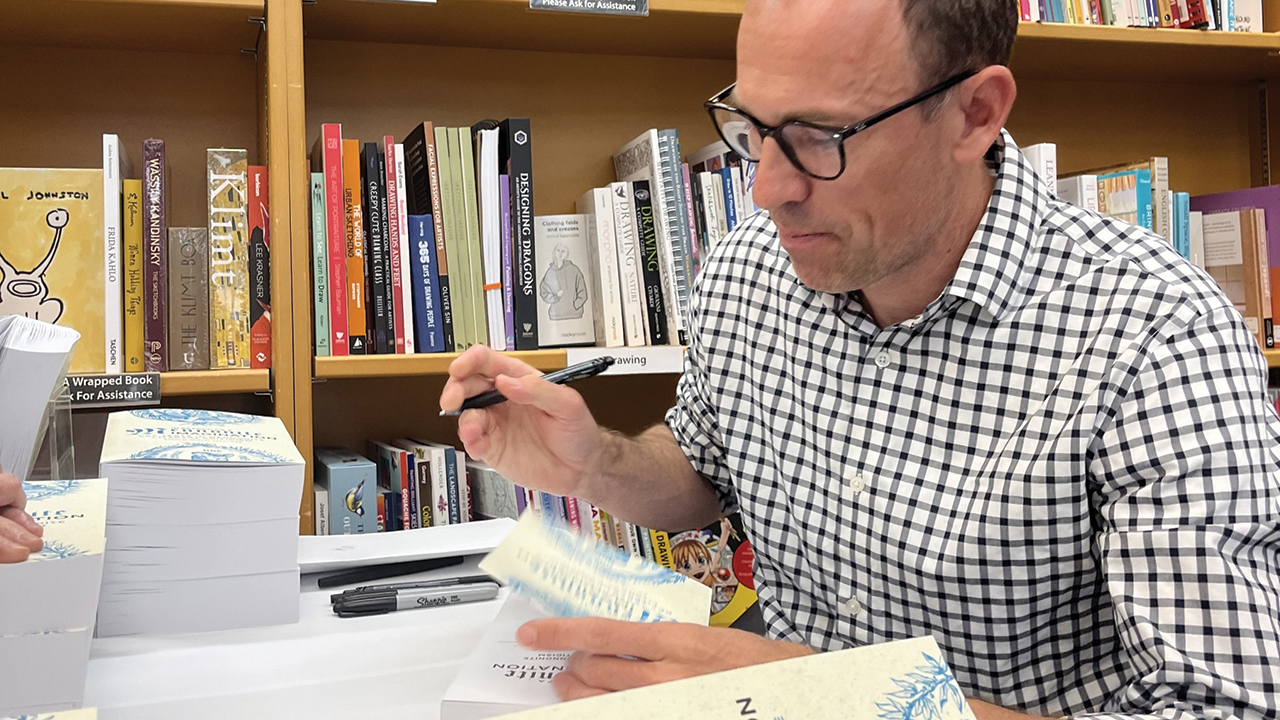

Robert Zacharias, an associate professor at Toronto’s York University, has collected 53 texts by 44 authors. “The hope,” he writes in his introduction, “is that this collection will serve as a meaningful record of where the critical conversation has been, and a resource for those who will extend it into the future.”

The book chronologically traces the evolution of Mennonite thinking about literature from the late 19th century, when church leaders warned Mennonites not to read fiction, to the 21st century, when award-winning Mennonite writers laud the merit of the authentic pursuit of a story. Zacharias has provided introductions for each author that speak to their prominence in North American Mennonite English-speaking literary circles.

In the earlier texts, Mennonites view fiction as a spiritual threat. “The evil against which I wish every lover of truth to array himself in full armor, is novel reading,” admonishes H.B. Burkholder in an 1873 Herald of Truth article. Five years later, J.H.M. argues in the same publication that reading by “our people” of the likes of the “Ten Cent novels of the day” is a slippery slope that could lead to “attending the theatres, ball room and fashionable picnics and forsaking the assembling of themselves together at the house of worship.”

Suspicion of fiction lessens, and by 1945 Mennonite scholar Elizabeth Horsch Bender expresses hope that a Mennonite author will publish a well-written novel. She asserts that the fiction that American Mennonites have written thus far about Mennonites is “trifling and undignified.” She adds: “Perhaps one of our colleges will produce a writer not only capable of writing well, but also of interpreting an ethical or doctrinal or social problem of the Mennonites in a work of imaginative literature.”

Three decades later, Margaret Loewen Reimer notes that “Mennonite literature has begun to flourish” but laments in an essay entitled “Can Mennonites Write Art?” that Mennonite writers haven’t yet discovered “what constitutes art.” She characterizes Mennonite fiction writers as writing for the “in-group” and adds: “If we Mennonites are to tell our story we will have to learn how to laugh at our foibles and dare to point our fingers at our failures. And ultimately we will have to transcend the Mennonite story to tell the human story.”

By the 21st Century, all doubts have been cast aside whether Mennonites can write art. I ponder how Horsch Bender and Loewen Reimer, if they were still living, might be delighted with the literary quality of Women Talking by Miriam Toews, Shelterbelts by Jonathan Dyck, As Is by Julia Spicher Kasdorf or The Practice, the Horizon and the Chain by Sofia Samatar.

While literary critics in the book celebrate Mennonite art, they also acknowledge that some Mennonites are offended by the portrayal of their practices or theology in some of this art. Ervin Beck lists a “canon of transgressive Mennonite literary works” in a 2015 essay and argues that negative responses by Mennonite lay readers should not be dismissed. He also encourages scholars to expand their study to works by “fine Mennonite writers” not in the “transgressive tradition.”

Interestingly, in a 2018 text, Miriam Toews, one of the writers whose work is listed in Beck’s transgressive canon, notes that “there are the Mennonites who would be offended by any representation whatsoever.” Her purpose, she writes, is to “serve the story.”

Contradictory ideas expressed by authors in the 10 texts at the end of the book — first published from 2012 to 2023 — give clues to different paths Mennonite writers may take. Hildi Froese Tiessen observes that Mennonite writers have moved beyond identity politics. At the same time, Casey Plett, who self-identifies as a “Mennonite transgender woman,” writes that identity is important, and she still wants to work with identity.

Froese Tiessen also predicts that as Mennonite writers become assimilated into mainstream society, Mennonite texts may lack distinction so that only a “trace” of Mennonite influence on the text can be found by readers who know where to look. Zacharias responds that the prediction by Froese Tiessen of the future “remains a ways off,” and he lists numerous works by well-established Mennonite writers and emerging ones that contain Mennonite characters or address Mennonite concerns.

A few authors provide ideas for how the field of Mennonite literary criticism could become more inclusive. Sofia Samatar suggests that the study of hymns and other songs around the world could expand the scope of Mennonite literature. Daniel Shank Cruz, who self-identifies as “a queer Latinx Swiss Mennonite,” writes that food writing could provide an opportunity to explore the intersection of identities.

The anthology is valuable for academics because it makes available many foundational primary sources about Mennonite literature in one compilation. It is also likely to be well-received by lay readers. It includes lively and accessible language and specificity about authors and their works that reignited my enthusiasm for Mennonite imaginative writing.

As someone of Mennonite heritage and a practicing Mennonite of faith, I see myself in works by Mennonite writers — even in a “trace,” such as an emphasis on social justice or community or the creation of characters who are just ordinary folks — and I appreciate this representation.

Mary Ann Zehr is Writing & Communication Program director and assistant professor of rhetoric and composition at Eastern Mennonite University.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.