A new biography profiles the man known as “Mr. Missions.” For 43 years, Joseph Daniel (J.D.) Graber (1900-1978) walked with the Mennonite Church as it moved from seclusion to engagement with the world.

Graber’s mission career began when he and his wife, Minnie, traveled to India in 1925. But his influence wasn’t only through overseas mission.

Leading the MC mission agency beginning in 1944, Graber spoke boldly against the racism that separated most Mennonite congregations — made up predominantly of people of European ancestry in the United States — from the African American and Latinx people in their communities.

One of Graber’s often-repeated phrases was, “Every church a mission outpost.” Mennonite congregations multiplied dramatically in the late 1940s and 1950s during his tenure as executive secretary of Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities.

However, writes R. Bruce Yoder in Sowing Seeds: J.D. Graber and the Vision for Global Anabaptism (Herald, 2025), it was common practice for these congregations to initiate mission work from a distance — up to 50 miles from the church’s location — considered sufficiently remote to “protect” their services from an influx of converts from other racial and ethnic backgrounds.

In 1951, Graber wrote in Gospel Herald, the MC denominational magazine: “What a travesty on the meaning of a New Testament church to have it made up of a group of self-satisfied and self-righteous people, loud and zealous in their profession of wholehearted Christian living and hesitating to allow their neighbors of a different cultural pattern to come in! Surely there is something wrong.”

One example of this kind of conflict took place in Chicago in 1952. White members of the Chicago Home Mission congregation objected to African Americans worshiping with them and feared their neighbors would vandalize their building as revenge for integration. The church council decided to bus Black Sunday school students to a neighboring Black church each week.

Graber wrote an emphatic response: “We dare not exclude [Black] children from our Sunday school nor the parents from our church services. To do so lines us on the side of prejudice and vested privilege. A New Testament mission dare not be on that side. If we represent our Lord and His Gospel, truly we shall always find ourselves out in front on these issues where it is dangerous, and not safely behind a solid front of prejudice” (emphasis in original text).

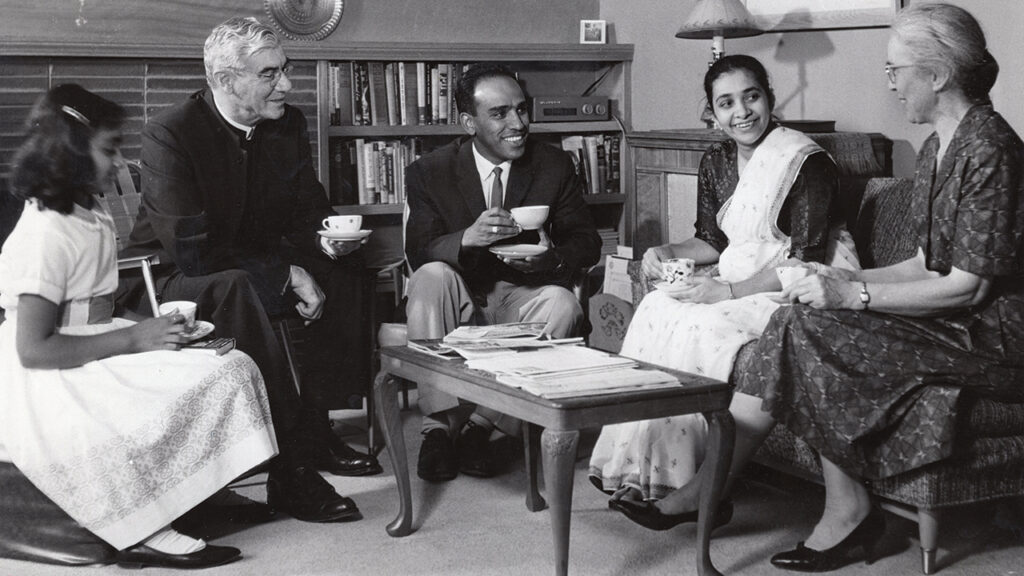

Graber also critiqued Mennonite ethnocentrism. He and Minnie had learned much from the church in India while serving there from 1925 to 1942.

In 1944, Graber became the first Mennonite mission executive with extensive cross-cultural experience. He was a fluent Hindi speaker and had immersed himself in Indian culture, which helped him understand the importance of dismantling colonial mission structures. He favored the “indigenization” of mission, a term that he used frequently throughout his life.

“As a firsthand observer of the Indian independence movement that Mohandas K. Gandhi helped lead, [Graber] understood better than most Western missionaries the need for new, postcolonial attitudes and approaches,” Yoder writes in Sowing Seeds.

As a mission administrator, Graber critiqued his own missionary work and was always looking for ways to move beyond the colonial mindset.

Graber served in leadership at Mennonite Board of Missions and Charities, a predecessor agency of Mennonite Mission Network, until 1967. During this time, he laid the groundwork for “a new day in mission” that is the basis for MMN’s partnership approach, in which mission workers are invited by partners to collaborate in God’s work.

This approach calls for a critique of all cultures, even as it seeks to contextualize the good news of Jesus Christ in a particular culture. It calls for mutual conversion of all involved in the mission endeavor.

Lynda Hollinger-Janzen writes for Mennonite Mission Network.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.