Hear this, you who trample on the needy and destroy the poor of the land, saying, “When will the new moon be over so that we may sell grain, and the Sabbath so that we may offer wheat for sale, make the ephah smaller, enlarge the shekel and deceive with false balances, in order to buy the needy for silver and the helpless for sandals and sell garbage as grain?” The Lord has sworn by the pride of Jacob: Surely I will never forget what they have done.

— Amos 8:4-7

The title above this passage in the Contemporary English Bible is “Judgment on Oppressors and Hypocrites.” I’m on board with that. I’m quick to pass judgment, and maybe you are, too.

Currently, in many Mennonite circles, we talk about those who oppress, rob, swindle and cheat. We protest. We call our legislators. We preach about the evils of empire and the sins of the world.

There’s much to pass judgment on. The brand of Christianity that many people see right now is, quite frankly, an embarrassment. Christians engage in the activities Amos describes, holding contempt for the marginalized and the poor.

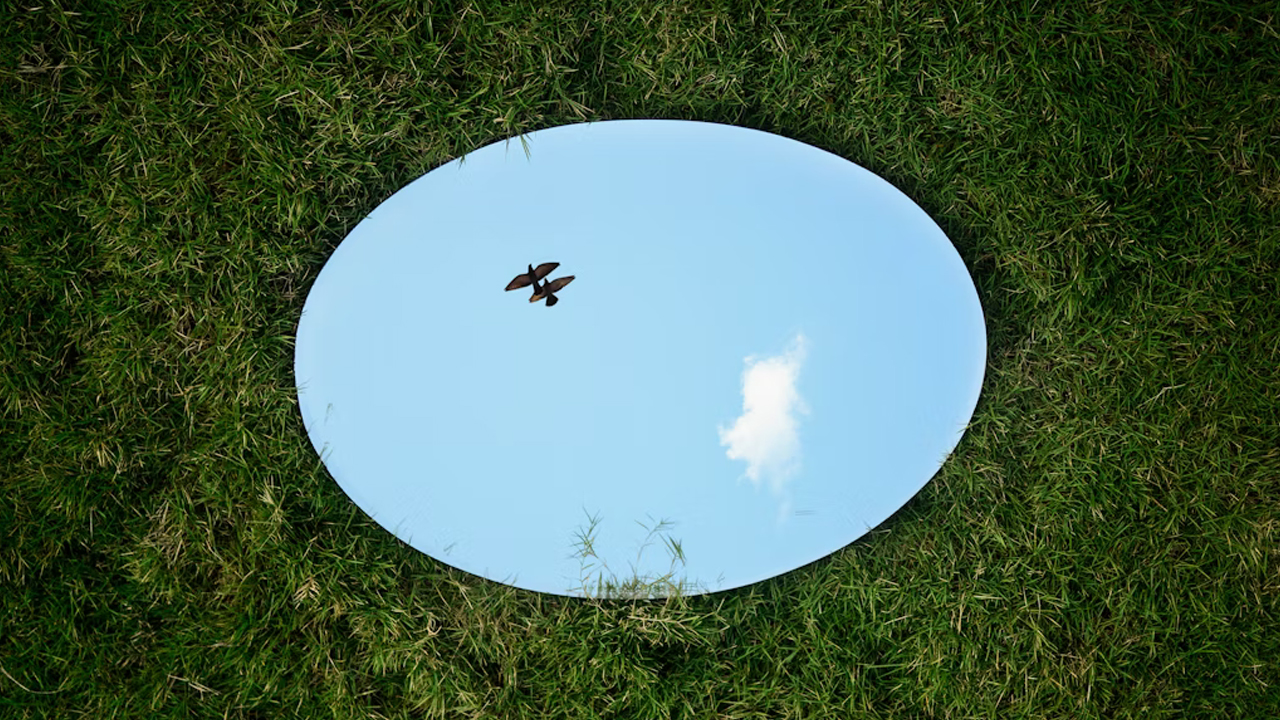

But lately, I’ve wanted to hold a mirror to my church — and, in that, hold a mirror to myself.

It’s easy to point to other churches. Churches that aren’t as “evolved” and “social-justice oriented” as we are. We can list our virtues: We take part in Mennonite Action. We’ve formed an antiracism task force. We give to those in need.

These are all great things, but none of us is blameless for making church too great a burden for some to bear.

For example, in several churches I’ve attended, it feels as if there’s a certain income threshold needed to belong. I’ve been told to move because I was sitting in someone’s regular seat. People of color have been tokenized — placed in roles to satisfy antiracism criteria — to make certain people feel better about themselves.

I don’t say this to condemn, because I take part in this as well. I have an income higher than many and have failed to be generous. I’ve allowed myself to be the token person of color. I’ve hogged the spotlight when it’s time for others to speak.

I can rail against the church all I want, and yet I am the church.

Lately I’ve not only been burned by the church but by myself and my actions. As Amos says, I’ve given God my garbage when I should have given grain.

Berating myself is not the answer, and neither is berating the church. I’ve been trying to stare at my reflection in the metaphorical mirror in an act of self-awareness rather than vanity.

One purpose of self-examination is to heal my relationship with the church — holding its imperfections in one hand and my own in the other. Another is to think of ways I can work at dismantling our systems that cause oppression.

Recently, during a learning event at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, I was made aware of these words by Carlo Carretto in The God Who Comes:

“How baffling you are, O Church, and yet how I love you!

“How you have made me suffer, and yet how much I owe you!

“I should like to see you destroyed, and yet I need your presence.

“You have given me so much scandal, and yet you have made me understand sanctity. I have seen nothing in the world more devoted to obscurity, more compromised, more false, and I have touched nothing more pure, more generous, more beautiful. How often I have wanted to shut the doors of my soul in your face, and how often I have prayed to die in the safety of your arms. No, I cannot free myself from you, because I am you, although not completely. And where would I go?”

Indeed, where would I go? Where better to go with my imperfections than the church, with its own imperfections.

I love this church. I need this church. This church — which can swindle, exclude and bear bad fruit — is a reflection of the people of God, who have themselves swindled, excluded and borne bad fruit. The church is us. It’s me.

It’s difficult to admit we are part of the problem. It takes humility to face our faults. But it’s the first step toward a solution.

Do we merely ponder the problem, or do we seek to transform it? The ethic of Christ — entering spaces others dare not go, inspiring faith and not automatically jumping to condemnation — should be both an outward and an inward act.

The world longs for transformation, a turning around. Maybe instead of pointing out others’ sins, I need to become an evangelist of transformation. While we protest, write, march and shout, I’m going to start including an invitation to be made new ourselves.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.