How praying for the nation’s ‘enemies’ led to a loving connection years later

Through our prayers God weaves a web that connects us to others in surprising ways. Much of the time this web is invisible, but once in awhile we catch surprising glimpses of it. My Aunt Velma told me a story about such a glimpse, a story that drew me into new connections as well.

It was December 1941 in an Iowa farmhouse. Supper was over. Papa and Mama pulled up chairs to sit, one on either side of the radio, listening intently. Never did they sit there like this after supper. There were dishes to wash, food to put away, chores to complete. But not tonight. Ignoring the waiting work, they sat there. Both were crying.

Velma knew something was wrong. She was not sure what, but her parents’ tears kept her in the room. Japanese planes had attacked American ships at Pearl Harbor, and President Roosevelt had declared war on Japan.

Papa and Mama explained that war was terrible—many people would be killed, many more injured, homes and belongings would be destroyed.

During the following days the patriotic fervor at school stood in sharp contrast to Velma’s experience at home. Her schoolmates said that everyone should go home and look at their toys to see if any were made in Japan. If so, they should take them outside and smash them with a hammer on the sidewalk. Confused, Velma reported this to Mama.

“No, Velma,” Mama said in her quiet, firm way, “that’s not what we should do. We need to pray for the people of Japan.”

Translating Mama’s response into her 8-year-old perspective, Velma decided to pray for the boys and girls of Japan. They were the ones with whom she could most closely identify. She tried to imagine what war would be like for them.

She thought of her most valued possession, her dearly beloved doll. How devastating it would be to lose her. She tried to imagine it smashed to bits in the remains of a bombed-out house. It was hard to fathom such a loss.

So she prayed for the boys and girls of Japan. Every night she prayed for these children who lived half a world away, who looked different from her and spoke a language she couldn’t understand. She imagined their families, their homes, their precious toys.

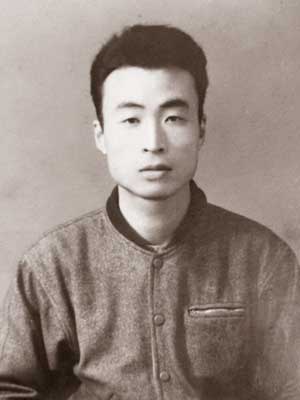

On the other side of the world, in Tokyo, lived Hiroshi, also 8. At first the war meant food lines and bomb shelters, but as the war progressed, the danger of bombing increased.

Hiroshi’s family, except for his father, who continued his job, and his oldest sister, who was required to work in a war factory, went to stay with relatives in Akkeshi, Hokkaido.

After Operation Meetinghouse, a massive bombing raid in March 1945 that destroyed much of Tokyo, Hiroshi’s father and sister decided to join the rest of the family in Hokkaido.

They packed their belongings and took them to a train station for shipping, but that night another bombing raid destroyed both their house and the station. Everything they owned was gone. It took them days to get a train to Hokkaido to join their anxious family.

The family struggled in Hokkaido. Among other things, they were not used to bitterly cold winters. Hiroshi had to work after school, going to a lumberyard to gather shavings, chips and bark for fuel. He could not understand why life had to be so difficult when what he really wanted was to play like his friends.

The winter after the war was even worse. The family was forced to search through garbage for potato peels and other food scraps. Hiroshi was so unhappy he thought of throwing himself off a cliff into the frigid sea.

The family moved to Obihiro. When Hiroshi was 18, he learned of an American missionary living there. He gathered up his anger-driven courage and went to a Sunday service, intending to let this American know how angry he was.

However, the morning did not go as he planned. Instead of unburdening his anger he found himself listening. The missionary’s halting Japanese made it difficult for him to understand the sermon and prayers, but a Japanese person read from Matthew 5, “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you.” He heard those words clearly. They caught his attention forcefully and followed him home.

Over the next months, surprise dawned slowly for Hiroshi as he learned that this American, Carl Beck, and the other Mennonite missionaries did not hate him but were genuinely sorry for the devastation their country had caused in Japan.

He was amazed there were Americans who not only believed in nonviolence but actually dedicated their lives to creating peace. While the missionaries introduced him to a new way of thinking about love and forgiveness, it was God’s loving welcome lived out by them that slowly began to dissolve the pain and anger that had shaped his growing up.

Back in Iowa, Velma married her high school sweetheart and started a family. She delighted in housekeeping and mothering and faithfully participated in her church community. She lived generously, always willing to help others.

In 1962, she and Dean, her husband, moved to Missouri to support a small Mennonite congregation there.

Hiroshi became a Christian and attended Tokyo Christian College to train as a pastor.

He returned to serve in the Obihiro church, where he met his wife, pastored the Asahikawa church, served as a missionary in Ecuador at radio station HCJB and then returned to Japan, where he served as pastor of the Nakashibetsu Mennonite Church until his retirement. In 1991, his son Kenji came to the United States to study at Hesston (Kan.) College.

Velma’s children grew up and married. Grandchildren came. The firstborn, Heather, completed high school and enrolled at Hesston College. When she came home with her Japanese boyfriend, Velma welcomed him warmly, as she did all newcomers. When Heather and Kenji married, her world expanded to include a Japanese family.

Kenji’s father came to Missouri to visit his son. One Sunday he spoke at church, telling about his difficult childhood and painful wartime experiences. He also told about meeting the Mennonite missionaries who introduced him to Christianity and how learning to know Christ had transformed his anger into love.

Velma was there. As she listened to Hiroshi’s story, she was startled to realize that they were the same age. His war experience triggered her memory of listening to the radio with her parents that somber, long-ago evening and her mother’s alternative response to the Japanese “enemies.” She remembered her prayers for the Japanese children.

Chills ran up and down her spine. Standing here before her was one of the children for whom she had prayed all those years ago. Those prayers were a faint memory. She had never given thought to seeing any tangible results, certainly none that would connect with her life.

Yet here in front of her stood Hiroshi, his life a testament to God’s power to heal and change. Without knowing him, she had prayed for him during some of the most difficult experiences of his life, and now he was here, not a nameless stranger but a member of her family.

She stood up, spine still tingling, and told her part of the story.

Prayer is a mystery. We often do not know what difference our individual prayers make. When they are about the specifics of our lives, we look for answers, but when our prayers are general we often let them go without specific expectation. Yet we pray, trusting that our prayers will make a difference.

Hiroshi might have met the Mennonite missionaries, and his son might have married Velma’s granddaughter even if she had never prayed for the “boys and girls of Japan.”

On the other hand, these things might not have happened. Ultimately, I can’t determine cause and effect, but neither can I let this story go with a shrug; it is too powerful.

Sir William Temple observed, “When I pray, coincidences happen, and when I don’t, they don’t.”

I think he would see a connection between Velma’s prayer and the miracle of healing from the wounds of war that touched not only Hiroshi but many lives on several continents.

Our prayers are part of a vast web of human longing woven together by God’s amazing power. Velma, Hiroshi and their families are enveloped in this web that has brought life-changing gifts to their lives.

That day in a small church in Missouri, the Iowa farm girl and the Japanese city boy touched a common strand of that invisible web and gave thanks for God’s astounding providence that connected them in such an amazing, “coincidental” way.

Kathleen Weaver Kurtz is a retired pastoral counselor ordained by the Virginia

Mennonite Conference. She attends Manassas (Va.) Church of the Brethren.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.