Gilberto Flores carries Jesus’ light into pain and darkness.

As two soldiers with guns came knocking at the door, Gilberto Flores—a former pastor in Guatemala whose ministry in Christ-centered peace and justice angered the corrupt government—quickly led his wife, Rosa, and three children in the kitchen …

As two soldiers with guns came knocking at the door, Gilberto Flores—a former pastor in Guatemala whose ministry in Christ-centered peace and justice angered the corrupt government—quickly led his wife, Rosa, and three children in the kitchen.

He remembered his boyhood in El Salvador in the 1950s. That’s when his parents chose to continue their free-church ministry in the face of persecution in the heavily Catholic region. He remembered when he baptized a man who later became president of Guatemala during the violence-ridden 1980s.

“We have come to kill you,” the soldiers said.

“Everything that God will allow you to do, you will do,” Flores replied. “But you can’t do anything that God doesn’t allow. … If you touch me, that will be the last thing you will do. God will judge you severely, because I am a man of peace.”

The soldiers looked at each other and left without saying a word.

This was only one of many times God’s mysterious intervention allowed Flores to walk away from death in Central America to share Christ’s life in North America. In the early 1990s, Flores left Guatemala to serve in the wider Mennonite church in the United States. It’s where in a variety of roles he’s helped the church more fully realize its missional calling to join God’s work in the world.

In an interview last spring, Flores, associate conference minister for Western District Conference (WDC) and former denominational minister for Mennonite Church USA, said he doesn’t want the earlier drama to overshadow the ongoing story of how Christ’s light has guided him forward. And yet, he hopes the story inspires others to risk taking Jesus’ light into the pain and darkness of their own communities.

“I grew up hearing my parents saying that if we will die, we are ready, but we will not stop doing what we are doing,” Flores said. “As a boy, my heart was marked with the belief that we are called to serve God, and if that costs us our life, we can’t control that. I grew up with a sense that our life is in God’s hands, and only God decides how we live it and how we lose it.”

Persevering family passes on passionate faith

God has shaped Flores, 67, from boyhood on, into a prophet who passionately prods people to take Christ out of the sanctuary and into the street. He was born on Nov. 25, 1945, in the small city of Santa Ana, El Salvador, the sixth of 10 children belonging to Pioquinto and Maria Cristina (Campos) Flores.

As a son of a Protestant pastor, his life at school was difficult, as prejudiced teachers and peers taunted him. But because of the modeling of his family, he absorbed these hardships into a backdrop of persevering faith.

“Every week, when we had choir rehearsal in our home, my father opened up the windows and doors so the strains of the hymns would waft out into the streets,” Flores said. “People from the community threw stones at our house. Even though my father had to clean up the mess and repair the roof, the next time he’d open even more of the doors and windows.”

Flores also remembers being told stories of the Christian martyrs who were persecuted for their faith and how in the 1930s his father was jailed 15 times for refusing to stop his ministry. Once he was beaten and left for dead.

“My parents went to minister in a little village, where a group destroyed the sanctuary and beat up my father,” he said. “My father lay there without help for two days. But when some people from a city church brought two caskets to bury my mother and father, they found Mother alive and Father still breathing.”

Like father, like son

This passion for ministry became Flores’ own. At 14, he witnessed about Jesus in school. At 16, he became a youth pastor and a deacon. At 18, he was licensed as a Christian education minister for 10 churches in El Salvador. At 24, he became a pastor of his first congregation as he finished seminary.

In 1972, at the age of 27, he met and married Rosa Herrera and was ordained pastor of a congregation in southern Guatemala. It was there that the first seeds of his peace and justice focus sprouted when he discovered how cotton farmers were being exploited with low wages.

“That pastorate was a turning point for me,” he said. “I was preaching and doing pastoral duties, but one day, I had an ‘ah-ha’ moment and realized I needed to approach the community from a more peace-and-justice angle. That was my first step into the messiness.”

His transformation as a pastor deepened in 1974, when he took his next pastorate in a rural village in northern Guatemala, where laborers received only 15 cents a day.

“I wanted to find new ways of making the kingdom of God more visible in the community,” he said. “By 1974, we were already facing the social turmoil of civil war. I could no longer preach love and peace from the pulpit without applying this to the poverty and violence all around us.

“I felt the pulpit wasn’t enough to make my ministry relevant in those circumstances. My place was to be with God among the suffering people and the outcasts.”

Flores’ missional-infused ministry incited conflict with government leaders. They recoiled from his bold stance in the pulpit and elsewhere, including a national day of prayer and fasting he organized in 1982.

The two kingdoms clashed one Sunday morning in mid-1982. That’s when the president of Guatemala, who began his Christian journey under Gilberto’s ministry in 1979, came to the Casa Horeb church to worship with a huge entourage of armed guards.

“I announced that he must take his people armed with weapons out of the sanctuary.” Flores said. “I said that this is holy, peaceful ground and that because of that he had to do as I requested. He said he wanted to be an obedient servant and so took out all his army helpers.

“After the service, I told him that he needed to stop doing unjust things and engaging in criminal actions, such as killing the poor. He later told me he could longer be my friend after all the disrespect I had shown him that day in church. It was a very sad and painful moment for both of us.”

Transitioning from Latin America to North America

His pain and betrayal ran deep, and Rosa’s health deteriorated due to anxiety and stress. But deeper still was their bond to Christ, and so they continued to move forward. For example, Flores became academic dean of the Mennonite seminary SEMILLA in Guatemala City and helped to launch the Association of Evangelical Churches in Guatemala.

The scope of their ministry made another seismic shift in 1990. The couple received a call from Eastern Mennonite Missions to become church planters in Caracas, Venezuela. After one year there, they returned to Guatemala. And in 1992, Rosedale Mennonite Missions (Conservative Mennonite Conference) asked them to help plant a church in San Antonio, where they remained from March 1993 until 1996.

As they prepared to move to Houston to take a new church-planting assignment with Rosedale Mennonite Missions, they received a call from Lois Barrett, then executive secretary of the former Commission on Home Ministries (CHM) for the former General Conference Mennonite Church. (It merged with the Mennonite Church in 2002 to become Mennonite Church USA.) She invited Flores to apply as the director of CHM’s Hispanic Ministries.

“At first, I was resistant to the idea,” he said. “It seemed God, through the opportunity to pastor a local congregation in Houston, was answering my prayers for not having so many responsibilities and the heavy emotional drain.”

But in the end, because of the encouragement of Rosa and others, he accepted the role. In June 1996, he and Rosa moved to Newton, Kan. It’s where he began his sojourn with what became Mennonite Church USA. And it’s where Rosa, also seminary trained and gifted in many ways, helped plant a new Hispanic congregation, Casa Betania.

In the next 13 years, Flores served Mennonite Church USA Executive Leadership and Mennonite Mission Network in several roles: as director of Instituto Biblico Anabautista (IBA), as denominational minister for Mennonite Church USA and as director of missional church advancement. In 2009, he left denominational work to nurture WDC’s Hispanic leaders and congregations.

Prophetic gifts till soil of church in transition

His prophetic ministry is a gift for a church seeking to be more multicultural and more missional, says Barrett, director of the Great Plains Extension of Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, and Jim Schrag, former executive director of Mennonite Church USA.

“He was a good fit for CHM for so many reasons,” Barrett says. “He was a pastor, he was theologically trained and he knew immigrant Hispanic culture in North America, and because of that, he knew what was needed. Plus, Latin America was focusing on the missional church long before we were. The scope of Flores’ missional understanding was formational and foundational for us.

“And his work with IBA has been a very important tool in developing Hispanic Mennonite congregations, because it educated folks theologically and connected them with the wider Mennonite church.”

Schrag says: “Gilberto often said to me, ‘Jim, you need to take risks. Being missional is all about taking risks and stepping outside the box. And congregations need to be active in this process for it to be effective.’ He was so interested in the persons in the pew and was well aware of the mental and cultural barriers that made it difficult for Mennonites to do these things.”

Schrag admires Flores greatly. He says: “He has tackled his challenges with the English language and culture and has become proficient and profound within them. He has lived in a bilingual world and yet has not played Anglos and Latinos against one another. And he has remained faithful to a church and its people even when he perceived they were moving too slowly.”

Daring the church to step over the threshold

Flores believes his challenges to the church were disorienting. He has prodded an oft-cautious denomination to embrace the liminal—the initial stage of a process that can be symbolized by stepping across the open doorway into another room.

“I am a dreamer and idealistic, and in a denomination like ours, people can tend to be more like technocrats and engineers than dreamers and risk takers,” he said. “It can be complicated to push through new agendas. Sometimes you engineer transition for so long that the initial passion dwindles. Sometimes in the kingdom of God, you’ve got to stop fitting the puzzle together and move with the Spirit.”

His overarching passion is tending the growth of missional theology and practices. And yet, tending multicultural issues are inherent in that focus, he said. His WDC work with Hispanic leaders and congregations gives him ample opportunity.

Even with all the hard work Mennonite Church USA has done in being a more multicultural denomination, the church still face challenges in opening doors to other cultures and dealing with tough issues such as immigration, he said. But he believes the church has made headway, especially its discussions regarding the anti-immigration laws in Arizona as they pertained to our 2013 churchwide assembly in Phoenix, he said.

“My remaining task is to finish creating a mission-oriented and multicultural conference and to see that we are putting WDC into the world and not outside it,” he said. “This is my hope before retirement.”

Slowing down, savoring God and family

The Flores’ ministry has led the couple, often at breakneck speed, down many dangerous and bumpy roads. So the couple is looking forward to retirement, although they are not sure how it will unfold, they said. They dream of going “home” to Guatemala.

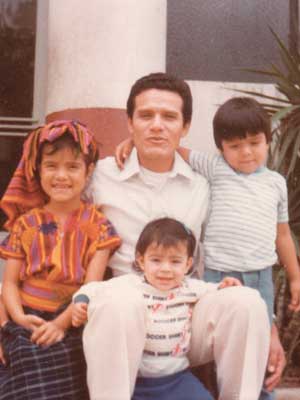

They talk of enjoying their four children—Keren, Gilberto Jr., Fabiola and Pablo—and their seven grandchildren. They relish resting in their love of God and family and to be grateful for four decades of marriage. After seasons of going to bed not knowing if they would wake up alive the next day, they hope to enjoy more togetherness and joy.

In his personal time with God, Flores always says thank you to God for God’s sense of humor in his life and the life of his family, he said. He often senses God saying that it doesn’t matter what happens in life, that there is always grace and a laugh at the end of the road.

“At the hardest times in our lives, when people were rejecting us, Rosa and I kissed each other goodnight and feared that may be our last kiss,” he said. “During this time, one day at 5 a.m., one of the poorest men in our congregation brought some bread and chocolate and said, ‘I have stopped by because I love you and want to spend a little time with you.’

“That moment was God’s sense of humor, consoling us with his presence through fellowship with this poor taxi driver. In ourselves, we could not have done and endured the things we did, but through God’s grace, as reflected in this simple moment, we learned not to take ourselves too seriously but to say ‘thank you’ for saving our lives.”

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.