As a young adult, Tillie Yoder Nauraine dreamed of working with urban children. Those dreams and her passion led to changes in many lives.

Tillie, who grew up Amish partly in Kokomo, Ind., but mostly in Holmes County, Ohio, had an abusive childhood, perhaps one of the reasons she took compassion on young children in need throughout her life and implemented programs to reach out to them.

“We were often sent after our own green switches either from the lilac bush or the peach trees in the orchard. … My father, all our life at home, read the Bible, had family prayers, attended church and lectured us on the meaning of the Bible. Yet our most painful experiences in life were at his hands,” she writes.

However, the beatings eventually stopped when she was around 13—after she and her younger sister temporarily ran away from home.

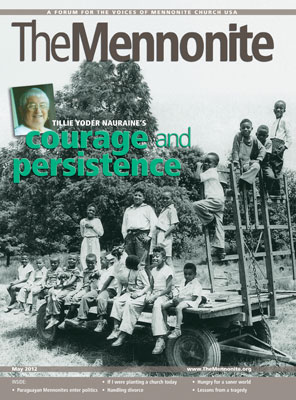

Then, in 1947, when Tillie was a young woman at Hesston (Kan.) College, she began a “Fresh Air” camp on her father’s farm for urban boys from Chicago. Earlier that year, Tillie went home to Holmes County, Ohio, for Christmas break. During that visit, she daydreamed about how to use an empty house on her father’s farm and soon realized she wanted to start a camp. Her father approved of her idea, and she enlisted help for that summer.

Tillie had moved to Hesston in 1946 from Eastern Mennonite College (now University), Harrisonburg, Va., which did not permit African Americans to enroll as students. This struck Tillie as wrong; she had an African-American friend from Virginia, Margaret Webb, known as “Peggy,” who wanted to attend Eastern Mennonite Seminary but was not allowed.

Virginia Mennonite Conference encouraged Peggy to attend Hesston (Kan.) College instead. In 1946, Tillie left Harrisonburg for Hesston with Peggy, according to Martha Ann Kanagy of Kidron, Ohio, who later became close friends with Tillie.

(In 1952, Peggy reapplied to Eastern Mennonite and became the first African-American student to graduate from the school, according to a 2011 article on EMU’s website.)

Camp Ebenezer

One significant helper at the camp on Tillie’s father’s land was her friend from Hesston, Martha Ann. The camp, then called Camp Ebenezer, stands as the forerunner of Camp Luz, now operated by Ohio Mennonite Conference. Laurence Horst, then director of Voluntary Service for Mennonite Board of Missions in Elkhart, Ind., assisted Tillie, along with nearby churches.

The first summer of camp was a homegrown affair for the boys from Chicago. Tillie wrote in an undated essay: “We cooked on a four-burner kerosene stove. We hauled water in milk cans on a wheelbarrow from the fresh water spring at the big house. Churches in the area laundered clothes. Swimming in the old Daughty Creek substituted for showers.”

However, the interest and participation of the children at camp amazed and impressed Martha Ann. “Some of the boys had to stay in tents because there were more than expected,” she said. “They had a great time and were well behaved.”

Camp Ebenezer offered Bible classes, recreation, nature study and more. While the programming included spiritual development, Tillie did not appear to support large altar calls or put pressure on the young campers.

“We do not believe that a mass hand-raising upon the invitation to accept Christ is adequate. We believe each child must make a personal decision, and he can do this only by coming to one of the staff and talking over his desire to be a Christian,” she wrote in a 1949 issue of Gospel Herald, the publication of the Mennonite Church at the time.

Many of the boys told Tillie and Martha Ann about how they disliked their schoolteachers back home and described their meanness to the students, which brought out the worst in the students. However, Martha Ann said that major disciplinary issues did not arise during camp.

Tillie also supported mutual relationships developed at camp between the staff and the campers. She planned trips for the camp staff to visit the homes of the children who came to camp.

“If the staff knows something of the homes, the communities and the environment in which the children live, it gives them a better insight into the needs of each child who attends camp,” Tillie wrote in an article in the Gospel Herald in 1949.

In another essay, Tillie named the publicity her camp received in Gospel Herald as a reason it thrived. It continued for four consecutive summers. Many individuals shared food, bedding, transportation and funds.

Over the years, scholars offered critiques to similar camp and Fresh Air programs. As Tobin Miller Shearer writes in his 2008 dissertation, “ ‘A Pure Fellowship’: The Danger and Necessity of Purity in White and African-American Mennonite Racial Exchange,” in few cases did the exchanges between the hosts and the African-American children lead to “involvement with African-American adults, civil rights marches or other action against racial injustice.”

Furthermore, the African-American children were subject to the standards of the Mennonite hosts. “Although the children gained travel and adventure, they did so at the cost of dealing with hosts who often tried to make them conform to a worldview based on prejudice and racism,” Miller Shearer writes. On the other hand, the children altered the adults’ perceptions of racial purity, as they forced the adults to reexamine their racial myths and expanded their worldview.

Bible school in Cleveland

In 1947, Tillie took a year off from college and worked in Wooster, Ohio, according to the 1986 book The Black Mennonite Church in North America by Leroy Bechler.

“She began to think that she wanted to do something closer to home,” says Vern Miller, 84, who knew Tillie from Goshen (Ind.) College and later planted the Lee Heights Community Church in Cleveland that grew out of a Bible school program, Gladstone Mennonite Mission, started by Tillie.

“Since home was Holmes County, Youngstown and Cleveland became her target,” says Miller. “She wanted to serve African-American communities in Ohio in the way the Larks were serving Bethel in Chicago.”

(Tillie met James H. Lark as a Hesston student when she volunteered as a summer Bible school teacher at Bethel Mennonite Church in Chicago, where Lark served as pastor. Lark was the first ordained African-American Mennonite.)

Miller, a student at Goshen at the time, says that Tillie asked him to join the Gladstone ministry. He agreed and spent two summers volunteering at the Bible schools. Miller stayed in Cleveland and planted a church in Gladstone in 1957 that closed due to an urban renewal program. Later, in 1959, he began Lee Heights, with the foremost goal of forming a “self-governing and self-supporting” congregation, according to Bechler’s book.

Regina Shands Stoltzfus, a Goshen College professor, writes in a Mennonite Life (Summer 2011) article that Lee Heights committed itself to this new model of “indigenous partnership.”

“People who lived in the host communities would have a say in the structure and culture of the new church,” she writes. Gerald Hughes, longtime music director, Eileen Friend, Alice Phillips and many community members played important leadership roles.

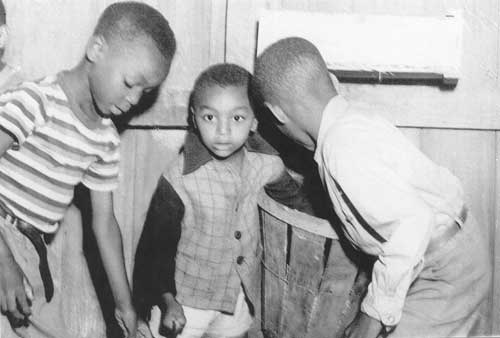

The Bible school program started when, one day during Tillie’s time in Ohio, she walked around one of the most depressed areas of Cleveland and came across a school. She talked with a principal about her vision of using the school for a Bible school program. The principal directed her to the board of education’s office.

This Bible school program in Cleveland required Mennonite signatures from Elkhart, Ind., and Aurora, Ohio, as well as permission from school officials in Cleveland.

“She looked [like a] very conservative Mennonite when she was downtown with the school officials,” said Miller in a Jan. 12 interview. “She had the courage to wait several hours. When they saw that she wasn’t going anywhere, they finally talked with her, and out of that conversation these Bible schools happened.

“In the summer of 1948, she had the use of those schools free of charge,” Miller said. “It was a miracle.”

The Mennonite Voluntary Service unit’s volunteers worked as the teachers, as did individuals from Plainview Mennonite in Aurora. The summer of 1948 had over 400 children, which “flabbergasted” the MVS unit, according to Bechler’s book. “The rest is history,” said Miller.

According to Bechler, the Bible schools attracted hundreds of individuals from 1948 to the early 1950s, and camping played a major part in the programming.

“Tillie Yoder’s vision of a spiritual ministry away from the inner city continued to bear fruit in Gladstone’s summer program,” writes Bechler.

“[Tillie] was persistent. She had a vision and followed it,” Miller said. “For me, she was an inspiration.”

On the edge of emotional catastrophe

According to the Mennonite Church USA Historical Archives, Tillie married Joe Nauraine from Goshen (Ind.) College in 1952, and they raised four children. They spent time volunteering at a boys’ home in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for five years and later returned to Indiana, then Iowa, where they both worked as social workers. They moved many times in the United States.

Despite Tillie’s legacy of service, her marriage with Joe brought pain throughout her life. She and Joe struggled in their relationship, causing Tillie to experience depression and frustration. In her autobiography she describes their marriage as “living on the edge of emotional catastrophe of one kind or another.”

She names Joe’s sexual identity and financial de-cisions as the most significant conflicts they faced.

Upon returning from their time in Puerto Rico, Tillie saw a therapist and concluded that she could live with Joe if she had adequate emotional distance from him. “I could never again be so emotionally bound up in him as I had been before,” she wrote. Joe later died, in 1975.

Later in life, Tillie returned to Goshen and began making ceramic dolls. She opened a doll shop and sold handmade dolls, many that she made. She also wrote children’s literature. In 2009, she sent her first book to the publishers—although her friends do not know the outcome. Tillie died on Feb. 27, 2010, in Goshen.

Anna Groff is associate editor of The Mennonite. Serena Townsend as a student at Goshen (Ind.) College was an intern with The Mennonite this spring.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.