True justice is not distinct from but rooted in mercy.

A severe, hard-bitten view of justice is all too familiar to us. “She got what she had coming to her.” “He was asking for it; lock him up and throw away the key.” “Three strikes, you’re out.” On the other side we have mercy: a soft thing that offers second chances, urges us to forgive and forget.

We tend to set up justice and mercy like equal and opposite forces and talk about the need to balance deeds of justice with acts of mercy as if there were a quota system for each or some magical formula for knowing when to do what. For example, when my children were young, I asked myself continually, Is this a moment to show justice by presenting consequences? Or a moment to show mercy by working around their silly demands? It can get confusing: We know how to be tough; we know how to be tender. But how do we know when to do what?

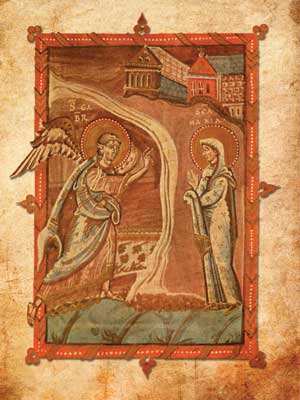

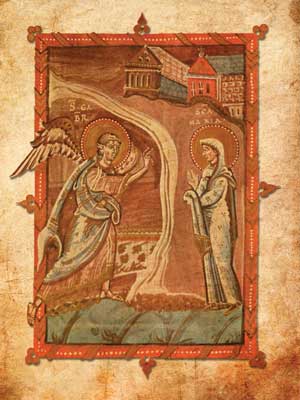

This separate but equal view of justice and mercy, however, was not the view of Mary, the mother of Jesus, as revealed in her song of justice, commonly referred to as the Magnificat (Luke 1:46-55). Instead, she wove the two attributes together into a stunning, seamless garment:

“His mercy is for those who fear him

from generation to generation.

He has shown strength with his arm;

he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts.

He has brought down the powerful from their thrones,

and lifted up the lowly;

he has filled the hungry with good things,

and sent the rich away empty.

He has helped his servant Israel,

in remembrance of his mercy,

according to the promise he made to our ancestors,

to Abraham and to his descendants forever.” (Luke 2:50-56, italicized phrases speak of mercy; underlined phrases speak of justice).

This wise young Galilean woman didn’t diminish justice into a crusading moment of searing righteousness; neither did she water down mercy into weak gestures of kindness. As the lowly were lifted up and the hungry filled, the tides of economic culture would be tipped so that the proud-hearted would be scattered, the powerful brought down and the rich emptied. The dominant, authoritative ones would be turned around in their boots. (Perhaps this is what God mercifully knew they needed to come to themselves.)

Mary understood that the sort of justice God dispenses flows with mercy because it reverses life’s unjust circumstances, as we know them. This penchant God has for turning the tables upside down is what Dallas Willard calls, in The Divine Conspiracy (HarperSanFrancisco, 1998), the Great Inversion: “There are none in the humanly ‘down’ position so low that they cannot be lifted up by entering God’s order, and none in the humanly ‘up’ position so high that they can disregard God’s point of view on their lives. The barren, the widow, the orphan, the eunuch, the alien, all models of human hopelessness, are fruitful and secure in God’s care.”

Yet this Great Inversion is not God’s arbitrary attempt to level the playing field but an offer of hope to those who have been denied hope and a challenge to trust to those who have not been forced to trust.

True justice is not distinct from but rooted in mercy. In God’s economy, justice and mercy often appear in tandem: “Thus says the Lord of hosts: Render true judgments, show kindness and mercy to one another” (Zechariah 7:9). Jesus scolded the carefully righteous, spice-rack tithing Pharisees for neglecting the “weightier matters of the law: justice and mercy and faith” (Matthew 23:23). Mercy and justice make natural companions in the person of Jesus Christ, who is described as “full of grace [mercy] and truth [justice]” (John 1:14).

How this amalgamation of justice and mercy helps us! When we truly understand it, we no longer have to wonder if this is a moment to be tough or tender. It’s always a moment to be tough and tender because justice and mercy complement each other: Justice is rooted in mercy and mercy often results in a surprising blaze of justice. Tough love is not hard-hearted but full-hearted, watching for faith and honoring it whenever it is found, hoping not to punish folks into oblivion but pull them back into the fold with grace and forgiveness. The picture frequently drawn of the Hebrew God who dispensed justice but neglected mercy is simply not true: “As I live, says the Lord God, I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked but that the wicked turn from their ways and live; turn back, turn back from your evil ways” (Ezekiel 33:11).

Personally involved

Mary also understood that God’s penchant for reversing circumstances manifests itself in intensely personal ways. God is not a bureaucrat, willing to invert circumstances only for the welfare of nations. Instead, God becomes involved in the lives of individuals loved by their Creator.

Even before Mary had to flee to Egypt as a political refugee, she knew that Judean Jews looked down on Galilean Jews as impure, backward, poor and ignorant. Yet the message of the angel was that the divine Messiah would not come from the exalted, pedigreed Jerusalem area but from her “tainted” Galilean territory and her impoverished Nazarene household-to-be. So God’s topsy-turvy way of dealing with folks was real to her. Once again, as Walter Brueggemann writes in The Prophetic Imagination (Fortress Press, 1978), God was creating an “unthinkable turn in human destinies when all seemed impossible”:

“My soul magnifies the Lord,

and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior,

for he has looked with favor on the lowliness of his servant.

Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed;

for the Mighty One has done great things for me,

and holy is his name” (Luke 1:46-49; italicized words and phrase indicate personal dealings).

One gracious upshot of understanding that God blends justice and mercy is a willingness to trust God, to want this God to “dwell in my heart through faith.” I begin to believe that God really does make all things work for “good” and that perhaps this good isn’t some brutal thing that will chafe and annoy me but a goodness sweet to the tongue. It makes me want to jump on board with this God and abide there. As I do, I explore the nuances of mercy and justice in each situation, seeing that God isn’t on one person’s side but on everyone’s side, weaving justice and mercy through each circumstance.

Being present to the voiceless

Mary’s example urges us to tag along behind God in lifting up the lowly and filling the hungry with good things. We are to pay attention to their plight (offering justice) and be present to their person (showing mercy). Our interaction with them is vital for our faith: It gives hope; it tests our automatic responses and normal gestures of respect; it teaches us to love as almost nothing else can.

My training ground in this occurs on Monday mornings working at the shower desk at a drop-in center for the homeless. There I fold towels, do laundry and hang out with folks who own less than would fill a small corner of my garage. Yet they’re always saying, “I’ll get by.” There I stand at the center’s shower desk—the longtime, learned Christian who teaches regularly on faith—seeing, hearing and touching faith that is greater than my own. I return home enriched.

One important way to offer a voice to the voiceless is respect. Dorothy Day tells this story in Loaves and Fishes (Orbis, 1963): “I had occasion to visit the City Shelter last month, where homeless families are cared for. I sat there for a couple of hours contemplating poverty and destitution in a family. Two of the children were asleep in the parents’ arms and four others were sprawling against them. Another young couple were also waiting, the mother pregnant. I did not want to appear to be spying since all I was there for was the latest news on apartment-finding possibilities for homeless families. So I made myself known to the young man in charge. He apologized for having let me sit there; he’d thought, he explained, that I was ‘just one of the clients.’ ”

While I, too, have been made to wait because I’ve been mistaken for being “just one of the clients” by police, social workers or the public health nurse, I’ve also been the one dismissing folks. I’ve caught myself feeling free to be rude to clients, to interrupt them while they’re talking. I’ve walked in front of clients without excusing myself, as I would never do with anyone else. I cringe to think that in the beginning of my years there I spoke a little more loudly to clients with poor English. (Now I warn new volunteers by teasing them: “They’re not deaf—only Latino.”) God’s voice murmurs to me as I work, “Do you see me within this person? I am here. Love me.”

All this speaks to me about how to practice a life woven with justice and mercy. It’s only after seven years of volunteering that I can respond to the rare client who is loud and abrasive by saying in a soft voice, “I’m sorry, but I can’t let you talk to me that way. If it continues, you’ll have to leave.” The odd mixture of justice and mercy often confuses them. They’re used either to being yelled at or catered to.

In the early days, I snapped back. Then, after a few years, I tried to be saintly by saying nothing but fuming silently. Mixing toughness and tenderness has only come by hearing their voices and honoring their presence as I practice God’s presence within.

Singing out of our soul

Sometimes we’re asked to follow Mary’s lead even further and speak up to family, friends and church members about giving a voice to the voiceless. Whether this is a response to their comment about a bag lady or a suggestion to a group that wants to serve, we speak up for the plight of the voiceless. What works best, I believe, is telling stories. I don’t have to preach or pontificate, but I can tell about heart-wrenching acts clients do for each other or that volunteers do when they think no one is looking.

But justice must permeate these merciful descriptions. We speak with integrity, without glorifying involuntary poverty. While acknowledging that many clients have made poor life choices, we still advocate mercy in the midst of justice. Seeing and hearing about acts of just mercy awaken folks from their numbness as nothing else does.

In this way, we join Mary in her song because, as Dorothy Day wrote, “We need always to be thinking and writing about [poverty], for if we are not among its victims, its reality fades from us. We must talk about poverty because people insulated by their own comfort lose sight of it.” Quoting her Catholic Worker co-founder, Peter Maurin, Day wrote (in Loaves and Fishes) that “the truth needs to be restated every 20 years.” Because I now live in a middle-class suburb, I seem to need to hear this truth frequently (every Monday to be exact) or I will lapse into a world of me, myself and I.

By and by, giving a voice to the voiceless changes us inside, as spiritual disciplines tend to do. It changes one of the worst of our errant core beliefs (which truly rule our feelings and behaviors even though we deny we believe them), that God is a scolding schoolteacher or angry drill sergeant. As we learn to speak to others with grace and truth, we no longer hear the voice of God in our minds nagging and taunting. Instead, the tone of that voice is gentle and full of reminders of truth. When someone else speaks of God as harsh (without mercy) or as weak (without justice), it feels downright wrong to us. We have tasted the grace and truth of God and savored it.

Every now and then we get to the place where an angelic person urges us to pursue radical justice and mercy that will make us appear foolish—and we say, “Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word.”

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.