Reflections from a trip to Jordan

In a region often identified with conflict, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan stands out as a place where peace and religious acceptance is both preached and practiced. Though I am a Mennonite who preaches (and tries to practice) peace, a trip to this land in the Middle East taught me much.

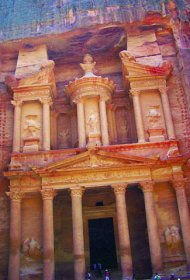

A huge tomb carved into the rock at Petra, one of the seven wonders of the world and Jordan’s greatest tourist attraction. Photo by Gordon Houser.

I traveled with 17 other Christian journalists from the United States and Canada. We represented periodicals that are part of three organizations: Catholic Press Association (nine), Associated Church Press (five, including me) and Evangelical Press Association (four). While the Jordan Tourism Board paid for our tour, JTB has no control over what I write here. And while it obviously wants to promote tourism, which is more than 10 percent of Jordan’s GNP, larger issues are involved.

Among the first places we visited was the Jordanian Interfaith Coexistence Research Center, housed in the Melkite Catholic Church in Amman, part of the Patriarchate of Antioch.

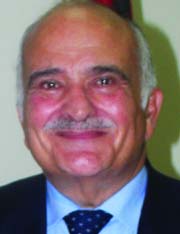

The center’s director, Father Nabil Haddad (pictured), told us his ancestors were at Pentecost (Acts 2). As Arab Christians they are living witnesses within a Muslim majority, making up about 5 percent of the population. (In 1950, Christians made up about 30 percent of the population.)

In answer to a question from our group, Fr. Haddad said that Muslims are not allowed to convert, according to sharia (Muslim law). “We don’t carry out missionary work because we want to keep what we have,” he said. Those who try to convert Muslims do more damage to Jordanian Christians than good.

Fr. Haddad pointed out that Arab Christians are in the Bible and in the Qur’an. The Prophet Muhammed was married to a Christian and welcomed Christians into his first mosque in Medina, he said. This kind of organization works in Jordan because there is no hostility between Muslims and Christians, he said.

Later that day we visited Prince El Hassan bin Talal, brother of King Hussein, who died in 1999, and uncle to King Abdullah. Having passed through security and been instructed to address him as “your royal highness,” we were taken aback when the prince came into the room unannounced and shook hands and greeted each of us.

“At the end of the day,” he said, “we all should support civil rights and sanctity of human life.”

He addressed so-called Muslim suicide bombers: “There’s nothing fundamentally religious about fundamentalists.” He called such actions part of the “hatred industry.”

He described governance as “good bedside manner,” knowing how to talk to people. Those who cannot live without war portray themselves as warriors, he said.

In order to put a halt to the hatred industry, he said, we must do something for people, especially the impoverished. And strategies against terrorism, he added, should address the causes, such as poverty.

He told a story of a time when some political leaders were visiting. He showed them some Iraqi refugee children who were sleeping in the street during the winter. They had nowhere to go. Leaders must keep such people in mind.

The Middle East does not have a way to discuss economics with a human face, he said. In 2050 there will be 55 million unemployed Arabs. At present, 60 percent of Arab youth want to migrate.

What is the role of Christians? he asked. We should study the texts of the other. Prince Hassan has done this. He gave each of us a copy of his book Christianity in the Arab World, which he wrote to help fellow Muslims better understand Christianity.

Interfaith dialogue, he said, should be talk about the practice of faith, not an ivory-tower conversation. It is necessary to bring people together and have a civilized framework for disagreement.

The next morning, we had a briefing with Senator Akel Biltaji. He explained that senators are appointed, as in the British system of government. They must verify every law the government proposes, then the king must sign it for it to become law. Jordan’s system of government is a combination of monarchy and parliament.

He offered a lesson in the history of the region and of Jordan, which became a nation in 1921-23 and became independent in 1946, moving from a princedom to a kingdom.

Jordan has been “an oasis of peace” in the region’s conflict, he said. Jordan is the second-largest peacekeeping force for the United Nations, he said.

He outlined what he called a 4-P process—piety, prophecy, politics, patriotism (the hijacking of religion)—which he said moves away from the core of religion, which is summarized by “love thy neighbor” and “love thy enemy.”

He gave examples of such hijacking of religion by Islamicists. “Jihad” is an inner war (self-denial), giving up pleasures for the sake of purity, he said, not a call to kill people. Jordan’s King Abdullah took leadership in opposing the violence of Islamacist terrorism, he said.

Jordan promotes not tolerance but acceptance of religion, he said. The Abrahamic path shows the commonality of the three faiths (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), he said.

He emphasized “peace through tourism”: leaving home for a purpose, earning knowledge, practicing people-to-people diplomacy.

In response to a question about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he said, “My cousins [the Jews] cannot see beyond their noses” and react out of fear; they cannot trust.

Through the week, we visited many sites of biblical and historical interest, including Gedara (where Jesus may have cast demons into a herd of swine), the Jabbok River (where Jacob wrestled with “a man”), the site of Jesus’ baptism, Jerash, Madaba (whose people are the direct descendants of some of the earliest Christians), Mt. Nebo (see Deuteronomy 34:1) and Petra, one of the seven wonders of the world.

On Oct. 2 at a hotel on the Dead Sea, I visited with Cindy and Daryl Byler over coffee. The Bylers are Mennonite Central Committee (MCC) representatives for the region that includes Jordan, Palestine, Iran and Iraq. They’ve been in this position for two years.

MCC has worked in Jordan for 40 years, they said, and 60 years in Palestine.

Primarily the Bylers help support the work of local churches and NGOs (nongovernmental organizations), both Christian and Muslim. They work with 15 groups in the areas of peacebuilding, community development and relief.

A large part of the work in Jordan is with schools, primarily Catholic and Anglican. Caritas Jordan, a Catholic organization, provides education about HIV/AIDS in many schools and also distributes MCC school kits. Jordan receives about 25,000 kits per year, more than any other country.

In Jordan, the Christian schools have a good reputation, Cindy said. Among the schools MCC supports are ones that work with special needs children, who are often seen as a burden or shame in Jordanian society.

Brent Stutzman is a volunteer with MCC’s SALT (Serving and Learning Together) program, working at the Holy Land Institute for the Deaf in Salt, Jordan. Volunteer Julie Lytle works at the Arab Episcopal School in Irbid, which is for blind and low-vision children in grades K-6.

MCC has begun working at East-West dialogue with young adults. The Bylers helped organize a meeting in Jordan of 13 young adults from the United States with young adults from the Middle East. This four-day conference has been held twice and done with the Middle East Council of Churches. MCC also sends two local students to the Peacebuilding Institute at Eastern Mennonite University in Harrisonburg, Va., each year.

Water is a huge political issue in the region. MCC helps villages build catchments to distribute water from springs. They also provide equipment and funding for materials.

Jordan is a place where the work of Mennonites, Catholics and others is welcome alongside that of Muslims. In a region where conflict is widespread, it is a place of peace where hospitality is valued and practiced.

Gordon Houser is associate editor of The Mennonite.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.