Colombian Mennonites are claiming and living out the story of the early Anabaptists.

Jaime negotiated the maze of motorcycles, buses, taxis, pedestrians and horse-drawn carts that jammed the streets of the Bogotá night. In the front seat, Leanne, my wife, made conversation, while in the back my son Josh and my daughter Allyson and I were silent, tired from a day overflowing with meetings and family visits.

Our visit with Jaime’s family that evening was one of many planned for us by the Teusaquillo Mennonite Church, a sister congregation since 2002 to Shalom Mennonite Fellowship, our congregation in Tucson, Ariz. This year, our family of four made up the delegation. It would be a two-week visit, a chance for us all to experience firsthand the face of the Anabaptist tradition in the context of war-weary Colombia.

Arriving at the apartment, Jaime sandwiched the car into its appointed space in the underground garage and led us up several flights of narrow stairs. The door opened, and there stood Ana, smiling broadly, beckoning us in. There were many introductions, handshakes and customary hugs. “This is such a special visit for us,” Ana said. “We never have the chance to meet with international visitors.”

She introduced us to three generations of family members, most of whom lived together in that tiny space, tucked away from public view. We soon found out why. They wasted no time launching into their story. The meal of arepas and chocolate would have to wait.

Ana’s family was one of successful entrepreneurs and community leaders. Their hometown, however, was located in a historic stronghold of the FARC guerrillas. Many in their community were campesino farmers, caught in the struggle between the advancing and retreating guerrilla and paramilitary groups who vied for control of the area. The FARC typically raised money by charging families a monthly “vacuna” (Spanish for vaccination), a sizable payment in cash or livestock to ensure safety and protection. Often in rural areas, those who refused to pay would often be targeted, their refusal seen as open defiance.

Ana’s husband’s family had been among those refusing payment of the vacuna, a decision for which they later paid dearly. Assassination of family members followed. Ana said such violence in her community was commonplace, almost expected. If in one week three people turned up dead, she explained, people said, “Well, at least 10 people weren’t killed this week.” In a context where violence was so rooted and prolific, there was an almost calloused resignation to the killing.

Despite the tragic loss of family members, Ana’s husband’s family initially did their best to remain, given their roots in that community and relative economic success. They hoped the killings had been sporadic, isolated events and that stability would return to their family life. But they soon learned from a friend with connections inside the guerrilla group that their family had already been targeted for slow but systematic elimination. And so, like millions of others in Colombia displaced by decades of violence, they made the difficult decision to leave behind all they had worked for and seek the relative safety and anonymity of the capital city.

By the time many of them managed to relocate to Bogotá, still others in their family fell victim to the threats. In the capital, 10 family members clustered together in one apartment to save money and tried to stay out of sight. But the FARC was well networked. It was not long before they located and captured the grandfather and laid out everything they were planning to do to the family, although he was later released unharmed. Shortly after, the family made the decision to file formal charges with the Attorney General’s office to denounce those pursuing them. They contacted friends and relatives in their home community to begin building their case.

But the decision backfired. It yielded the family no justice and only served to widen their circle of friends and family who were now considered targets. Before long, the accumulated stress weighed so heavily upon Ana that she had a complete physical breakdown and had to be hospitalized for one month. With time she regained some strength, but their danger remained acute, and many in the family began applying for political asylum to Canada.

It was months later that the family’s story began to turn. Ana received a call from a sister whose case had since been approved and had relocated to Canada. This sister had been sponsored by a Mennonite congregation there, and she was so overwhelmed by the support and love she had received that she commended the Mennonites to Ana and her family back in Colombia.

Ana followed up on her sister’s counsel and found her way to the Teusaquillo Mennonite Church in Bogotá. There they felt themselves immediately drawn to the community where, for the first time, they heard the gospel of forgiveness and reconciliation. They heard it proclaimed that violence and war were not the will of God.

They met members of the community, themselves ex-guerrilla, ex-paramilitaries and victims of violence who by the power of the Spirit had received and extended God’s forgiveness and accepted God’s way of peace. They worshipped alongside one another not as enemies but as brothers and sisters, modeling in deed the very community of peace that was being proclaimed in word.

In short, Ana and her family were awestruck and overjoyed by this good news. There had been many churches in their hometown, both Protestant and Catholic, but none of them had proclaimed or modeled such radical alternatives to the killing and violence, which continued unabated in their community.

At Teusaquillo there were healing services. There were Bible studies. There were prayer groups. In the safety and solace of these meetings, Ana and her family cried their first tears of pent-up grief, and the Spirit’s work of transformation brought change. They clung to the words of the Scripture they were given. They shared one such passage with us that evening, one they had claimed as God’s unique promise for them: ” Violence shall no more be heard in your land, devastation or destruction within your borders; you shall call your walls Salvation, and your gates Praise. The sun shall no longer be your light by day, nor for brightness shall the moon give light to you by night. … The Lord will be your everlasting light, and your days of mourning shall be ended” (Isaiah 60:18-20).

As we listened to their family’s story unfold, the entire room seemed to lighten, and their countenance visibly changed when they reached the point in the story where they discovered the church. They shared more examples of the radical difference the church had made in their lives (although they were by no means at that moment completely out of danger).

Ana recounted how one evening there was a gathering at the church. Many displaced families were present as always. These included, by definition, ex-guerrilla, ex-FARC, their ex-victims and other members. While they were gathered, the electricity went out, leaving them all together in the dark. Ana recalled how the meeting quickly turned into a party, with impromptu games and celebrations. They had so much fun together that no one left the church that evening until midnight. This illustrated for Ana how radical the transformation had been in the lives of the congregation’s members, who months and years prior had been mortal enemies.

Ana’s mother followed with a story no less astounding. She recounted how several months after she had joined the church she had been walking one day through the streets of the capital. It so happened that she came face to face on the sidewalk with one of the gunmen she had known to participate in the killing of her brother. Somehow she was able to extend the gift of grace she had so recently received. She told her brother’s gunman that she forgave him for what he had done and that she held no bitterness in her heart for him. She proclaimed to him God’s love and forgiveness. There in the street, they embraced one another and the man broke down in tears.

As I listened to her recount these events, I was struck by the similarity of her story to the ones I had grown up hearing in Martyrs’ Mirror, stories of my own Anabaptist forebears who had openly forgiven their tormentors and bore witness to God’s love that surpassed the violence around them. And here I was, in this tiny, crowded apartment in Bogotá, Colombia, at that moment surrounded by this once broken family, who were now claiming and living out the story of the early Anabaptists for themselves.

During our two-week stay, we met other families whose stories rivaled similar depths of pain and joy. It was a privilege to witness our sister congregation being a place of unconditional openness to so many broken people, so hungry for the words of hope they proclaimed and modeled. No less astounding was the way many of the displaced families, though often in grave danger themselves, assumed a similar posture of service in the church, working alongside others in ministries of feeding, healing and education.

This was true even as they struggled to regain safety and equilibrium in their own lives.

I perceived no visible distinction here between the “personal gospel” and the “social gospel,” as often seems the case in North American churches. Here it was simply the gospel, bound together and proclaimed in all its fullness: personal salvation, forgiveness and release from one’s past, the call to service and the way of non-violence. It should be no wonder, I suppose, that this message, when placed against the backdrop of such extreme violence and inhumanity, continues to make the church a compelling community for displaced families such as Ana’s.

For many in Colombia, daily life presents many obstacles over and above what we would consider normal for our context. But thankfully, the miracles keep pace. The Teusaquillo congregation maintains a weekly feeding program in a neighborhood replete with street people and addicts. They prepare food packets for distribution as they interact with those in need.

On our second Sunday there, Adaia, who helps regularly with the feeding program, shared what had happened the night before. They had arrived with some 300 food packets to find about 600 street people anticipating their arrival. They quickly saw their predicament and did what they so often do in the face of yet another obstacle. They prayed. Then, they handed out the food packets. What they experienced that evening was the multiplication of their “loaves and fishes” to the point of everyone being fed, with food left over.

I found it hard to believe they considered something so dramatic almost commonplace.

It all seemed such an alternate reality to the life of sufficiency and abundance that I lead. (Somehow the gospel looks different through the lens of job security and a retirement plan.) While I do not mean to discount the God I know here, whom I often experience working more through subtleties and distinguished shades of gray, Colombia for me was a more pronounced version of the kingdom in black and white.

And while I remain an “ethnic” Mennonite who can trace his biological lineage all the way back to my 16th-century Anabaptist roots, it was in Bogotá that I came face to face with my Anabaptist forebears and the God they walk with each day.

Erik Yoder is a member of Shalom Mennonite Fellowship in Tucson, Ariz.

A church with no walls or ceiling

Pastor Martin Gonzalez’church has no walls or ceiling. Not even a level floor. But if you look past the cardboard shacks of his congregants, clinging to the side of the ravine, it’s a beautiful view: lush green mountains, crops in bloom, a few brightly painted houses sprinkled around the valley.

Three years ago, he and Elsy, his wife, left the salary, benefits and four walls of their more traditional Mennonite congregation with a burden for the marginalized families of Anopoima. Anopoima is a small city in Colombia that is quickly gentrifying with moneyed families. With no more than a guitar, a Bible and some food or used clothing, he trekked to the ravine on the edge of town where the families were squatting.

Among others, they met Alicia, a wheelchair-bound girl barely in her teens. The house was cobbled together from scavenged pieces of metal and scraps of wood, its floor irregular and rough, difficult for even an able-bodied person to negotiate.

Martin used his video camera to document and publicize the living conditions of these fragile families. They openly petitioned government officials to follow through on promises to relocate the families to newer housing developments.

“We think Jesus and Menno Simons would have made the same decision,” Martin says. “But it has been scary for us. We didn’t always know where the food or tuition money for our children would come from. But God has been so faithful in providing for us each day.”

While they still visit the people on the hillsides, Martin and Elsy continue their pastoral work with many of the original squatter families in the new housing development where they now live. The fruits of their ministry are already evident as they walk from door to door, greeting their congregants. Children are clean, bathed and healthy. Grandmothers beckon them inside. Second-story additions are already under construction.

Martin and Elsy’s decision to set aside their secure income and build the church on the edge of town is but one of many stories in Colombia of pastors who have taken up the cross. Like Martin, many such pastors would desire a sister church in North America. They have much to teach us about the road of faith.

If your congregation is interested in exploring the possibility of a sister relationship with a Colombian church, you may contact Amanda Guldemond at iglesiashermanas@justapaz.org.—Erik Yoder

The sister-church relationship

In January 2001, the Teusaquillo Mennonite Church in Bogotá, Colombia, proposed a sister-church relationship with Shalom Mennonite Fellowship in Tucson, Ariz. With pastor Peter Stucky and two other members who were visiting the United States, they brought a small folder of photos and descriptions of their congregation and its ministries.

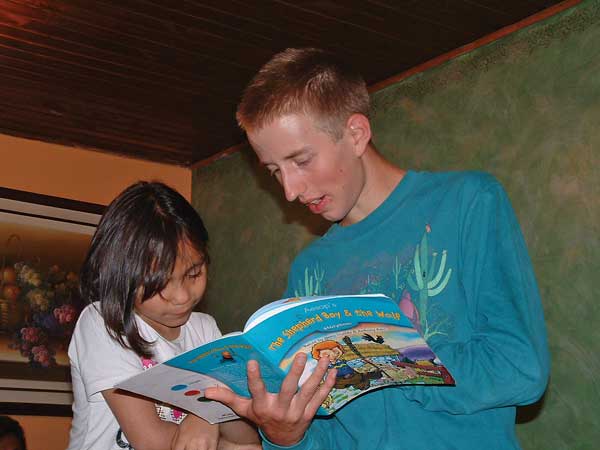

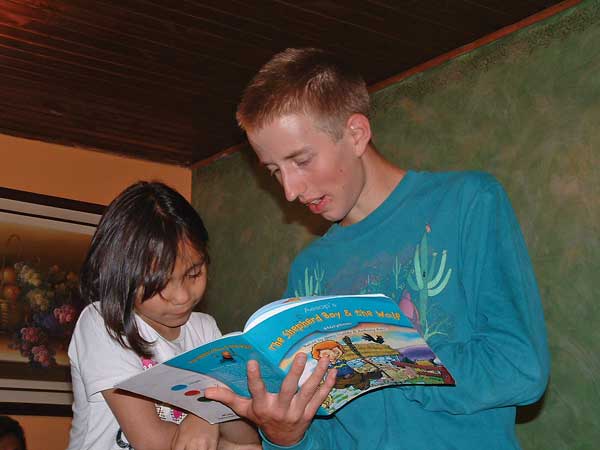

The relationship has evolved and grown since then. A delegation from Shalom has gone to Colombia every year but one to experience what church looks like in Bogotá. More than 15 members of Shalom have visited, some a second time. The Teusaquillo congregation has sent representatives to Tucson as well. This past year, one of its young adult members served in the local voluntary service unit as an outreach to the homeless.

In recent years, the two congregations have collaborated to open and later renovate a feeding center and after-school program for children in a high-need neighborhood. They have also cosponsored a greeting card recycling program providing income to displaced women in the capital city.

Last year, the Shalom delegation delivered 84 handmade lap blankets made by congregants and friends in Tucson and throughout the United States and Canada. The blankets were gifts for the residents of Hogar Cristiano La Paz, a nursing home sponsored and operated by the Mennonite Church in Colombia.—Erik Yoder

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.