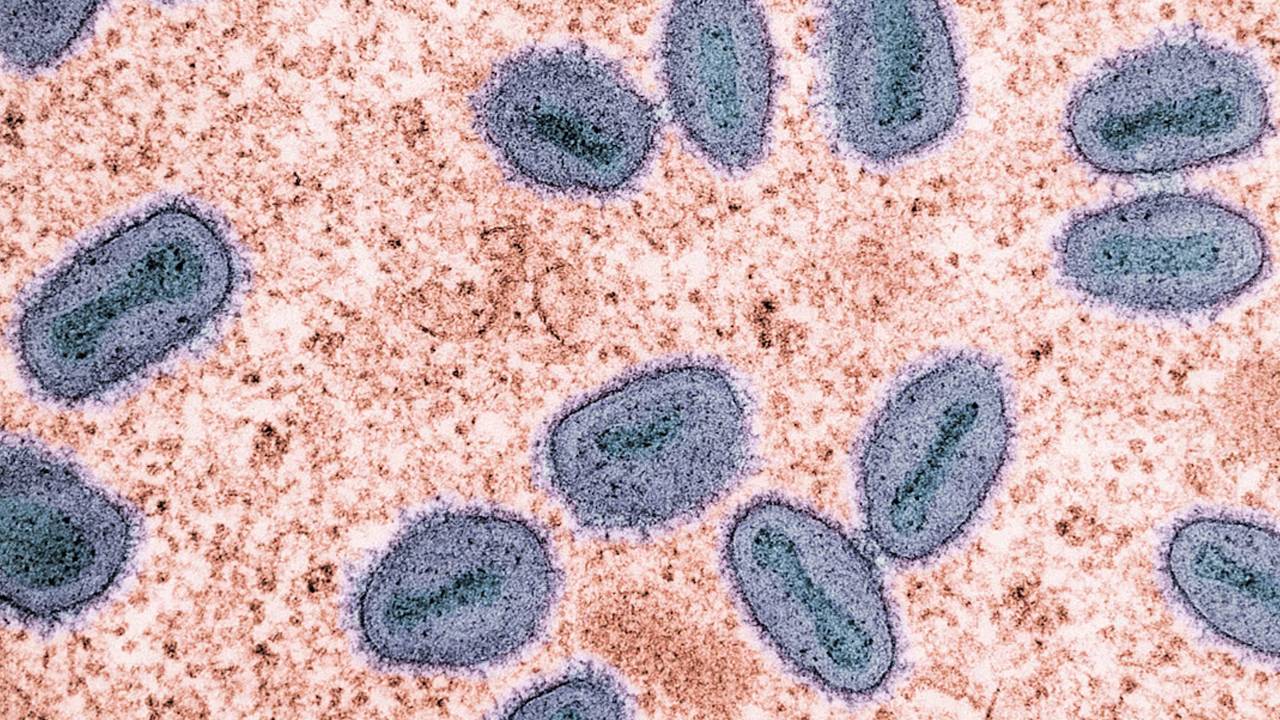

A typical adult human body, I recently learned, contains more microbial cells than human cells. Indeed, non-human cells — bacteria, viruses, and fungi, collectively known as the human microbiome — comprise roughly 57% of our bodies. Most of the time, these organisms live in a symbiotic relationship with the human body. Among other things, they aid in digestion, regulate the immune system and protect against pathogens. But occasionally some of those same microbes threaten the body in the form of infection and disease.

In Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines and the Health of Nations (Ecco, 2023), cultural historian Simon Schama details the fascinating story of this delicate balance, especially as it has played out in modern pandemics such as smallpox, cholera and the plague, which have led to the deaths of untold millions. Schama’s primary focus is on the counterintuitive, frequently controversial discovery that small doses of those same lethal diseases, administered in the form of inoculations or vaccines, can provide immunity against the diseases themselves. Paradoxically, the thing that seems to threaten the body most also bears within itself the promise of health.

I’ve been pondering these mysteries ever since, not only for their biological complexity but also as a rich metaphor of our own complicated social, political and religious moment.

At one level, Schama’s book has made me somewhat more understanding of the Low German-speaking Mennonite communities in Texas, Ontario and Alberta whose resistance to measles vaccinations recently fueled an epidemic that has led to the death of several children. Anti-vax sentiment, whether among conservative Anabaptists or devotees of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., is rooted in a deep cultural tradition, usually having less to do with religious convictions or a wholesale rejection of modern medicine than with a populist suspicion of government mandates, especially in matters of health.

But the recent national news stories about Mennonite resistance to vaccinations have also prompted other reflections about what it means to be a “foreign body” in a modern nation- state. To be sure, I wish that Low German-speaking Mennonite communities would vaccinate their children. I lament the needless deaths of innocents who had no voice in the decision. I wish these groups would recognize that their choices have consequences not only for themselves but also for the public at large.

At the same time, however, I also consider myself to be part of a religious minority — a microbe, perhaps — within the larger body politic. And like my Low German Mennonite cousins, I, too, want to have the courage to resist popular opinion even if that resistance runs counter to accepted norms — indeed, even if it seems to threaten the health of the nation-state.

From the very beginning of the Anabaptist movement, those in power regarded them as an alien presence. Sixteenth-century Swiss authorities frequently described Anabaptists as a cancer or a plague that threatened the health of their society. Yet at their best, religious minorities are an essential part of the social body, crucial to its well-being. The contrary convictions they uphold serve as a check on the presumption of the powerful and the self-serving prejudices of the majority. Their courage to resist accepted norms has often preserved ideals and principles that promote the well-being of the whole.

Here in North America, Anabaptist groups of all sorts have enjoyed a long period of religious freedom for which I am deeply grateful. But even a nation that honors religious liberty needs to define some limits. No one, for example, would defend a group’s right to commit child sacrifice.

What, then, should authorities do with statistics that predict with certainty that a certain percentage of children will die if they are not vaccinated? What is the line between religious freedom and cultlike control? When does a microbe become a pathogen?

Those same questions need to be addressed self-critically within Anabaptist groups, where sorting out which convictions are essential to Christian faithfulness is an ongoing challenge. All of us — progressive and conservative Anabaptists alike — are highly selective in the convictions that define the boundaries of resistance. Sometimes our narrow focus on specific issues may divert our attention from the deeper political and economic ways in which we are being absorbed into the body politic.

Within the complex living organism of modern society, what is the right image for thinking about communities of faith who are committed to follow in the way of Jesus? Are we an alien presence? A microbe in a symbiotic relationship? An inoculation against death-dealing diseases? Or simply another cell in the larger body?

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.