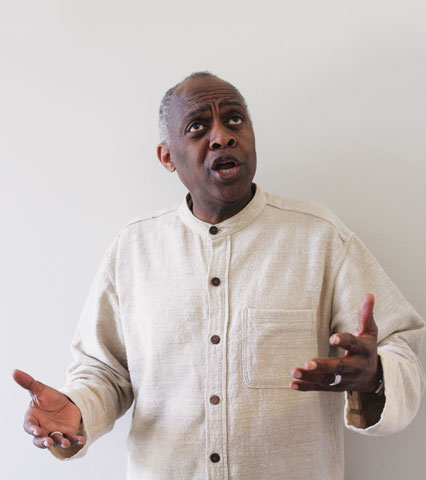

Tony Brown, who teaches at Hesston (Kan.) College, has used his singing talent to bring peace around the world.

“My world was turned upside-down,” says Tony Brown—who found himself the only African-American in he classroom as an 8-year-old in 1956. However, the school superintendent took Tony to other classrooms to sing. The other young children received his musical talent graciously––making a step toward breaking down racial barriers.

Tony, 61, was born in Pittsburgh in the Hill District––a group of neighborhoods considered the cultural center of African-American life in the city. Tony’s father spent his life as a pressman for the Pittsburgh Courier, a major African-American, nationally-syndicated newspaper. Later his father worked for the Post-Gazette.

Avid newspaper readers, Tony’s parents noticed an advertisement for a house and 10-acre farm for sale in the McDonald, Pa., area. They purchased the home and moved there with the hopes of enrolling their six children into a more rigorous school system. Tony’s parents believed education was the key for success for their children, although both of them had 10th grade educations.

Tony, who felt the call to use music for peace at age 8 in those classrooms, now teaches at Hesston (Kan.) College and is the school’s artist-in-residence.

“I’m still trying to listen to that call,” he says.

Although the Oliver Brown vs. Board of Education ruling dismantled the legal basis for racial segregation in schools in 1954, Tony (no relation to Oliver Brown) was not welcome in some settings. But his singing voice offered security. For example, Tony remembers a neighbor woman who yelled at him and his siblings as they walked to the bus stop. This woman did not like the man who sold his house to the Brown family; she took out her anger on Tony and his siblings. Later, Tony learned that the woman chaired the school board and had argued with the superintendent, who encouraged Tony.

When the neighbor woman screamed at him, Tony remembered his mother’s words, “Don’t say anything, but repeat Psalm 23.” His mother helped him understand that this woman was misinformed and a victim of her own fears. In fact, Tony’s mother even paid visits to this woman’s house, and later, when Tony was in high school, he learned that some members of that woman’s family actually ate dinner at the Browns’ house.

“My parents may not have been formally educated, but they were very wise,” Tony says. “I knew a lot about peacemaking from my family even before I was introduced to the Mennonites.”

This nudge to attend a Mennonite school came out of years of his aunt hoping Tony would become a minister––a desire that Tony’s mother prayed when she was pregnant with him. In Tony’s family and extended family, everyone wanted this for him.

“At some level, I thought of myself as somebody who was going to make some kind of mark,” Tony says, “but I didn’t know what that was.”

Tony found himself attracted to Kidron and Central. On Sunday of the retreat and after the tour of the school, the youth attended Kidron Mennonite Church. Tony heard a cappella singing for the first time.

“I was moved,” Tony says. “When the man took his pitch pipe and blew into it, the group sang as though they were a choir.”

Tony spent his junior and senior years at Central Christian. Back in Pennsylvania, he had attended a school with students from Polish, Irish and Italian backgrounds. But in Ohio, the Mennonite students were mostly of Swiss-German descent.

“They had a profound sense of community and were identified by the church they went to,’ he says.

He was the only African-American student at that school, but there was an African student from the Republic of Niger––with whom Tony shared a host family. Tony calls this cross-cultural experience “life-changing.” His time at Central also provided self-exploration.

“At Central, I became a little more self-confident about my gifts,” he says.

Tony easily made friends with his peers, too, although he was breaking ground in 1965 as the first African-American student at Central Christian. Tony admits he faced some social challenges, such as limitations in the girls he could date.

“You’re 16,” he says, “you’re AA, you’ve got personality, people like you—that could be potentially threatening to some parents.”

Teachers at Central introduced Tony to Anabaptist martyrs who died for their faith. Tony says the martyrs’ courage and strength impressed him. He studied Mennonite history at the same time the civil rights movement was “shaking up this country,” so naturally he drew comparisons between these groups of people.

In his commencement address at Hesston College on May 9, Tony again made the connection to 20th-century martyrs.

“I was moved by the courage of these 20th-century martyrs who [also] died for their faith,” Tony said. “Both narratives––while situated in unfortunate cultural circumstances––transcended culture. Following Jesus is not something that needs the prerequisite of culture, race or nationality.”

In addition to his faith development, Tony also “sang an awful lot” at Central—especially under the encouragement and instruction of music teacher Robert Ewing. His musical experience in high school culminated at graduation, when Ewing assigned Tony to conduct a choir of his peers.

After his high school graduation, Tony planned to attend Prairie Bible Institute in Alberta, since he intended to become a minister or missionary. However, his plans changed after talking with Esther Diener—the mother of his friend Larry—who steered him in another direction. She questioned the fit of that school for Tony and told him that some people at Prairie Bible considered Martin Luther King Jr. a Communist.

Soon after, Esther called Tony’s parents and then called Tillman Smith, Hesston’s president, to refer Tony to Hesston. Smith accepted Tony without a formal application. One week later, Tony made the trip to Hesston with his friend Larry and his parents.

“My getting to Hesston College was fortuitous,” Tony said in the commencement address this year, “and president Smith and I had many conversations about that in the years that followed. I felt so honored to know him and later to be able to call him my friend.”

At Hesston, Tony immersed himself in more music and considered making music his major. He also enrolled in many Bible classes. Tony cites his music instructor, Lowell Byler, as an individual who moved his musicianship to the next level. Byler saw Tony’s musical promise and helped nurture him personally and professionally.

After Hesston, Tony went on to finish at Goshen (Ind.) College, where he continued his involvement with music. There, his mentor, Atlee Beechy, told him to keep singing and use it for peace. Tony earned his B.A. in psychology at Goshen in 1971.

During three years at Goshen, Tony came to the conclusion he did not want to be a pastor, despite his family’s wishes.

“I had good people skills and compassion for people,” he says. “But I wasn’t interested in preaching.”

In 1973, he married his first wife, Joann Sprunger. In 1979, he earned his Master of Social Work degree at the University of Pennsylvania. From 1980 to 1983, Tony taught at Goshen.

But in Goshen, Tony faced an extreme act of hostility (see sidebar below). On Mother’s Day in 1983, some arsonists set the back of Tony’s house on fire, damaging the carport and totaling his car.

“When you’re an African-American,” he says, “and something like this happens to you, you have to ask if you’re a victim of a random act or if this is an overt racist statement. How can you prove that?

“Racism is etched into the psyche of this country and operates at the conscious and unconscious levels,” Tony says. “As long as I’m African-American, I’m going to be vulnerable to racial incidents occurring to me or other people of color that I know. … We still live in the legacy of Jim Crow. Even at the highest levels of our church, racism is a problem.”

In 1983, Tony and Joann moved to Seattle, where he spent 17 years as the assistant director of the counseling center at the University of Washington. He also taught in the graduate school of social work. While there, he studied voice with renowned baritone Julian Patrick, and his work with Patrick moved his music career to another level.

In 2000, Tony began teaching at Hesston. This year, Tony finished a tour, “Common Threads,” with Hesston faculty member John Sharp. The program gives voice to Anabaptist martyrs and enslaved African-Americans by singing their hymns and telling their stories.

Shari Leidig-Holland, a member of Pittsburgh Mennonite Church, first met Tony at the Cross Cultural Youth Conventions in the late 1970s and at the “black caucus” meetings for the Mennonite Church that she attended with her family. Later, Tony was Shari’s social work professor at Goshen College.

“He was an inspiration to me in that context as we talked about justice and equity as it related to the vocation of a social worker,” she says. “I resonate a lot with Tony as a fellow psychotherapist engaged in what it means to be a peacemaker.

“I think his connection between art and music and peacemaking is needed so much in our world,” she says.

Tony’s new major project, “Peacing It Together Foundation,” brings together his musical ability, his passion for peace and his love of travel. The foundation was officially founded in 2007.

The project’s mission statement says it is “to serve the global community as a resource and catalyst for the work of peace and social justice, using music and the spoken word to uplift areas of despair to hope.”

The hope is to provide musicians who have a passion for peace the opportunity to use their music to promote peace and justice around the world.

Although the foundation did not begin until 2007, Tony’s first peace-related trip occurred in 2002.

“The seeds of this organization were planted and come out of my early childhood years as well as out of a Mennonite context,” he says. “This is an outgrowth of the peace work Mennonites do. We’re just trying to extend it through the use of music.”

Tony offers several stories from his travels that demonstrate the power of music in bringing about peace.

When in Bosnia in 2002, he sang for a group of people that embodied the different sides of the conflict there. Serbs, Croats, Muslims and Jews all gathered in the standing-room-only concert hall. Tony thought he would sense tension in the room. But after he had the audience sing together several times, everyone softened.

“That evening of singing was incredibly electric,” he says. “I found that doing music there was more than just giving a performance. … Something transformative happened.”

This 2002 event laid the foundation for Tony’s current work, now extended to other countries all over the world.

In 2007, he took one of three trips to Northern Ireland sponsored by the Quakers. He attended a meeting between the leaders and their families of two major paramilitary groups—the Irish Republican Army and the Ulster Defense Association. Along with Irish folk singer Tommy Sands, Tony told stories, sang and led the audience in singing. Afterward, one man thanked them for coming, and the man wept. Leaders from the two paramilitary groups continue to meet and use music when they come together.

In May 2007, in Ethiopia, Tony brought together Orthodox Christians and Muslims—who remain in tension with one another. Muslim chanters joined Brown. But the Christian leaders prohibited the Christians from joining the stage and sharing it with Muslims. However, the individuals talked and greeted one another during the reception following. Brown believes the music in the concert set the stage for interaction between opposing sides.

Now back in Hesston, Tony’s work involves planning for visits to the Philippines, East Africa and West Africa. The West African trip came about when he received a phone call from people living in Ghana, Ivory Coast, Togo and Nigeria who want him to visit for a month this year. However, it may be rescheduled to 2011.

“The prospect of that is really exciting for me,” he says, “particularly in Ghana, where the slave trades occurred.”

Tony traveled to Uganda in June 2009 to bring supplies and equipment to the Anthony Brown Comprehensive School, which serves formerly abducted child soldiers in northern Uganda. The trip was made possible through fund-raising efforts by Hesston Mennonite Church. He made his first visit to Uganda in 2006, when he laid the cornerstone for the school.

He will travel to Mexico in December to perform and speak on behalf of the Mujeres de Maiz Opportunity Foundation, an organization that aims to provide resources for indigenous women in rural central Mexico who want to further their education. In October, Tony plans to travel to Haiti to sing and speak in an attempt to assist in trauma reduction in the earthquake aftermath.

While Tony’s membership continues at Seattle Mennonite Church, he attends Hesston Mennonite. This fall, he and Erika, his wife, will move to Albuquerque, N.M., for Erika to continue her education. Tony will continue working for Hesston––teaching classes online, continuing ambassadorial work for Hesston College and returning to campus every three weeks.

To read Tony’s blogs about his trips, go to www.anthonybrownbaritone.net, and for more information on his foundation, go to www.peacingittogether.org.

What I’m doing transcends race

People of color are often racialized when people want to write about them. One could ask all the women when interviewing them to tell about the many incidents of sexism they experienced in their lives, but this is not standard practice. I am not ashamed of my life experience, but what I am doing transcends race and connects people. My life is so much more than any negative racial experiences I might have encountered, and this is where we can focus. When we get to the place where we transcend the social construct of race when relating to each other, we will have advanced civilization. My life as a citizen of the world is much larger than any personal experiences with race I might have experienced. I am amazed at the many times I have seen in my travels how people can meet each other at the common places of human experience. Our human connections to each other are profound when we can get past our tendency to magnify how we are different.—Tony Brown

Anna Groff is associate editor of The Mennonite. Photos not provided are by Vada Snider.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.