Leaving the Argentine Chaco is no easy matter for two Mennonite mission workers.

I once sat with the late Marcos Esteban, a Toba elder in the Argentine Chaco, and talked through the leaving of another fraternal worker.

“We have been tied together with a ribbon of friendship, of fraternal bonds,” Marcos said. “We are brothers. Our lives are intertwined. One cannot simply cut the ribbon and throw the shorter end away.”

How, Marcos wondered, can someone depart to live out their lives, leaving him with only the memories from a long-term relationship?

In our highly mobile society we come and go, friendships are picked up and dropped quickly. We find it impossible to maintain relationships with more than a few close friends and family and depend on printed words and electronic technology to do even that.

For people steeped in oral cultures, the reality seems different. One’s web of relationships is extensive. While travel and communications media is less accessible, memory is more vivid. Physical encounters may be scarce, but distance is bridged more readily in a mythical worldview. They tell us that paradise, for them, is tranquility surrounded by family.

To leave and never come back, one must find an acceptable rationale.

This year, we left the Chaco after 38 years as part of a Mennonite team of workers from across the world, whose purpose in Argentina is solely to walk alongside indigenous Toba, Mocoví and Pilagá believers.

With our indigenous sisters and brothers, we began talking about leaving well ahead of time and listened to expressions of their feelings and thoughts. Remembering shared experiences as well as God’s work in their lives and ours over the years was an important aspect of this process.

While we talked about our impending leaving, one Toba pastor said, “I don’t like it when people often say, ‘If we don’t see each other again here on earth, we will see each other when we meet in heaven.’ I would much rather say, ‘Let us be in touch with each other through our prayers.'”

Since we arrived in the Chaco in 1971, it seems we have been called upon repeatedly to explain why it is necessary to maintain a missionary presence there. “After all,” some observed, “the indigenous church is, as you have told us, functioning well in a culturally appropriate way. They are on their own. Why should we stay? There are many places in the world where our church’s money is needed to meet more urgent needs.”

Since Mennonites began accompanying believers in the Chaco in the 1950s, one of the constant questions has been that of continuity. Why should a missionary presence be maintained? And what should we do?

Early in our ministry, Albert Buckwalter, who served with Lois, his wife, in the Chaco for more than 40 years, told me a story.

“When we announced we were no longer intending to be in charge of the Toba church,” he said, “the questions that inevitably surfaced were, Are you leaving us, then? Will you also now abandon us?”

“Only when we assured them we intended to continue to stay beside them did they feel the freedom to take full charge of their own church life.”

At the time, there was no model to understand this new church-to-church relationship. No one had heard of expatriate mission workers ceding control of the indigenous church to their own leaders, with no paternalistic intent to get the new churches into the denominational fold.

The term “fraternal worker,” which replaced “missionary” as a designation of Mennonite workers in the 1950s, has been fruitful. On the one hand, it describes clearly the more appropriate relationship between expatriate worker and local indigenous church leaders. (Albert once described the relationship in a Gospel Herald article, “Brothers, Not Lords.”) At the same time, it freed the indigenous church to designate its own “missionaries,” thus dignifying their own church. Recently, we have used the term “missionary-as-guest” in a further attempt at clarification.

We expatriates must not rob the indigenous leaders of both the privilege and the responsibility of being fully in charge. Will we, then, after being in long-term relationship with them, cheat them out of participating in the decision about whether we stay or leave?

In our world, the pattern of the missionary who established, defined and guided the young church is well entrenched. Indigenous church leaders in the Chaco have feared that the mission workers would abandon them once the foreigners were no longer in charge. Those fears persisted until it became evident the Mennonites did not intend to leave.

As we leave, we go with similar fears. If no workers come to join the Mennonite team in the near future, it will mean an almost total eclipse of accompaniment of the Pilagá churches. In recent years, earnest but culturally insensitive workers have arrived from other outside groups who enter to evangelize with a conquering spirit. The void of a fraternal presence in those churches will likely be filled more and more by evangelical groups with theological emphases that discourage genuine indigenous expression.

That expression is vital for the health of the indigenous churches, and unusual among evangelized indigenous communities. There must be some kind of continuity in our face-to-face interaction, even if it isn’t constant. Otherwise, the memory is broken. Interchurch solidarity falls into oblivion.

When the Buckwalters simply could not continue visiting the indigenous communities due to health concerns, they struggled with the commitment not to abandon the indigenous believers. Was that the Buckwalters’ personal commitment or was it made on behalf of the particular part of the body of Christ relating to the Chaco indigenous believers?

Surely Albert did not anticipate a perpetual North American presence among the Argentine indigenous churches.

Or did he?

We understand eternal life as a new quality of life, an unending participation in a new peoplehood in which we care for each other. Such is the church of Jesus Christ. We and the indigenous believers with whom we have established a spiritual relationship have become part of one body. There is a real sense in which that unity cannot be broken.

What is our ongoing responsibility to unity?

In the Chaco we have often pondered the meaning of the following widely spread quote from an Australian aboriginal activist group, as voiced by Lilla Watson: “If you have come to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

The question raised by this piece of wisdom has to do with our Western individualism versus an indigenous interconnectedness. It is an invitation to embrace the future with recognition of the basic unity of all that is.

That we might really need the contributions of those who have been left out until now seems too far out for our Western worldview to grasp. Can we really believe, in any substantial sense, that our future is bound up with that of others to whom we relate, especially if they are on the margins of human history? Or do we continue on our way believing we can relate to others when and how we choose?

Westerners have the power (read: economic domination) to decide if and when we initiate or terminate a relationship with those perceived to be weaker than us. This is similar to the way our consumer culture has taught us to discard anything that is no longer of service to us.

Jesus’ way of reading the narrative of his own people highlighted the value of the rejected ones. The stone the builders rejected has become the cornerstone of God’s historical project.

God’s project is to redefine the meaning of the “survival of the fittest.” In Jesus, the definition of who the fittest for survival are is reversed. The weak, the compassionate and the poor are God’s choice in building for the future survival of creation.

In light of the above, we as a church, as Mennonite Mission Network, seek to empower the marginal of the earth to live the Jesus way. We ought to do all we can to remain close to those who are God’s predilection for the future, in order that we not be left ignorant and with our liberation less than complete.

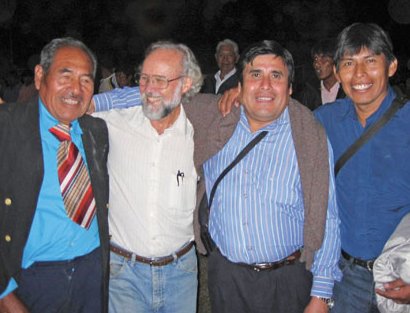

Willis Horst, with Byrdalene, his wife, served since 1971 with Mennonite Mission Network as part of the Mennonite team of six families walking alongside indigenous Toba, Pilagá and Mocoví Christians in the Argentine Chaco.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.