Maria will have a difficult decision to make in September when her legal documents allowing her to live in the United States expire.

She could stay in the U.S., risking deportation and living under the radar, so that her young teenage daughter, a U.S. citizen, can continue living in her country. Or she could move back to Venezuela — a country embroiled in humanitarian and political crises so severe that 7.7 million people have fled — after 16 years in the U.S.

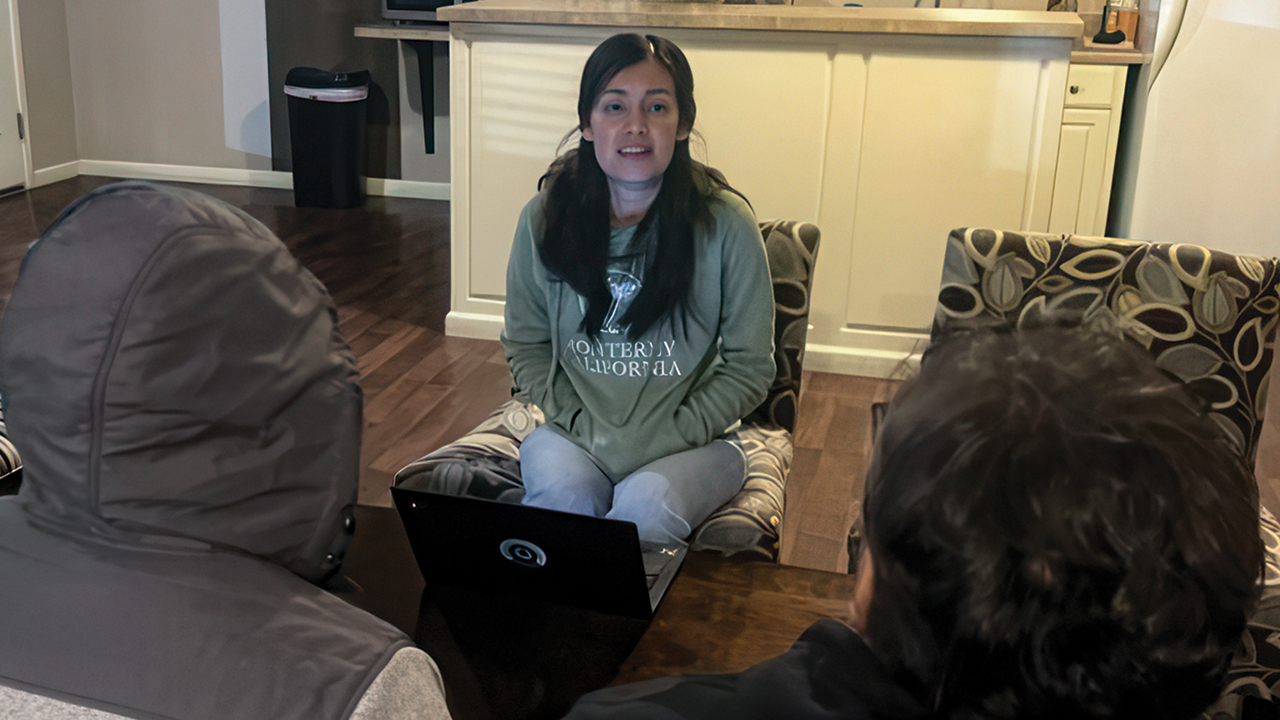

Maria (not her real name) came to Mennonite Central Committee East Coast immigration attorney Rachel Diaz to see if she has any other options to remain legally after her Temporary Protected Status expires.

Like other immigrants, Maria’s fear and concerns about living in the U.S. without documentation have spiked since President Trump instructed Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents to apprehend 1,000 to 1,200 immigrants a day.

Diaz said Maria had no legal options to stay, despite a clean criminal record, unless Trump extends TPS for Venezuelans.

Instead, Diaz advised her to make sure she has a family preparedness plan so her daughter would be taken care of in case Maria gets deported.

The plan includes actions, such as:

— Finding a trusted person to care for her daughter;

— Signing state forms giving that trusted person permission to care for her daughter;

— Having a valid passport for her daughter so she can fly to Venezuela.

“I have girls, too,” Diaz said. “And here I’m telling this mom who I know has been working to give her daughter a good life — she’s a good woman — that there’s nothing, no legal recourse for them at this point. So, that was tough to say.”

As immigrants witness enforcement happening on the news and in the streets, with and without a warrant, calls to MCC immigration staff increased.

Immigrants are asking for ways to get documentation so they can stay in the country. They want to know how to protect their children and assets in case they get deported. Pastors are inquiring about what to do if ICE agents come to their churches.

MCC’s immigration staff, especially in California and Florida, respond by meeting with clients and groups in churches and schools. And they listen.

“Sometimes I spend a good 20 minutes with people on the phone trying to listen to their situation, trying to calm them down,” said Crystal Fernandez-Benites, an immigration legal case worker for West Coast MCC. Sometimes there is no legal option, but “the accompaniment, the having someone, an organization where they can trust and go for guidance — I think that’s very important.”

Staff across the country are giving increasing numbers of “Know Your Rights” presentations in churches, schools and communities. Participants learn steps to take if they are apprehended and how to exercise their rights. They include:

— Exercise your right to stay silent.

— Don’t sign anything except an agreement with your own attorney.

— Carry copies of your immigration documents with you.

— Don’t open the door unless the ICE agent shows a warrant signed by a judge with the name and address of someone living in the house.

— Memorize a phone number to call from detention. (Don’t rely on your cell phone.)

One woman who attended a training in California said she was distressed by the increased ICE activity.

“I go out feeling afraid. I only go out for the essentials, and I ask God to protect me,” she said. “For me, this [training] was good because we need to be prepared and know our rights.” She now has an appointment with MCC to start the immigration process.

Fernandez-Benites said the first concern she hears from those attending the training is about their children.

“These are people who have been in the community for a very, very long time,” she said. “They have lives made here, and they have kids who were born here, and they are minors.”

A pastor who hosted a West Coast MCC training for her congregation of immigrants said she and her husband, also a pastor, have been asked by at least three families to be their children’s temporary guardians.

“They say, ‘Who else can we trust? We don’t have any relatives here.’ And if they do, they are in another state, and most of them are undocumented, too,” the pastor said. She and her husband agreed to support them because “the church is here to help.”

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.