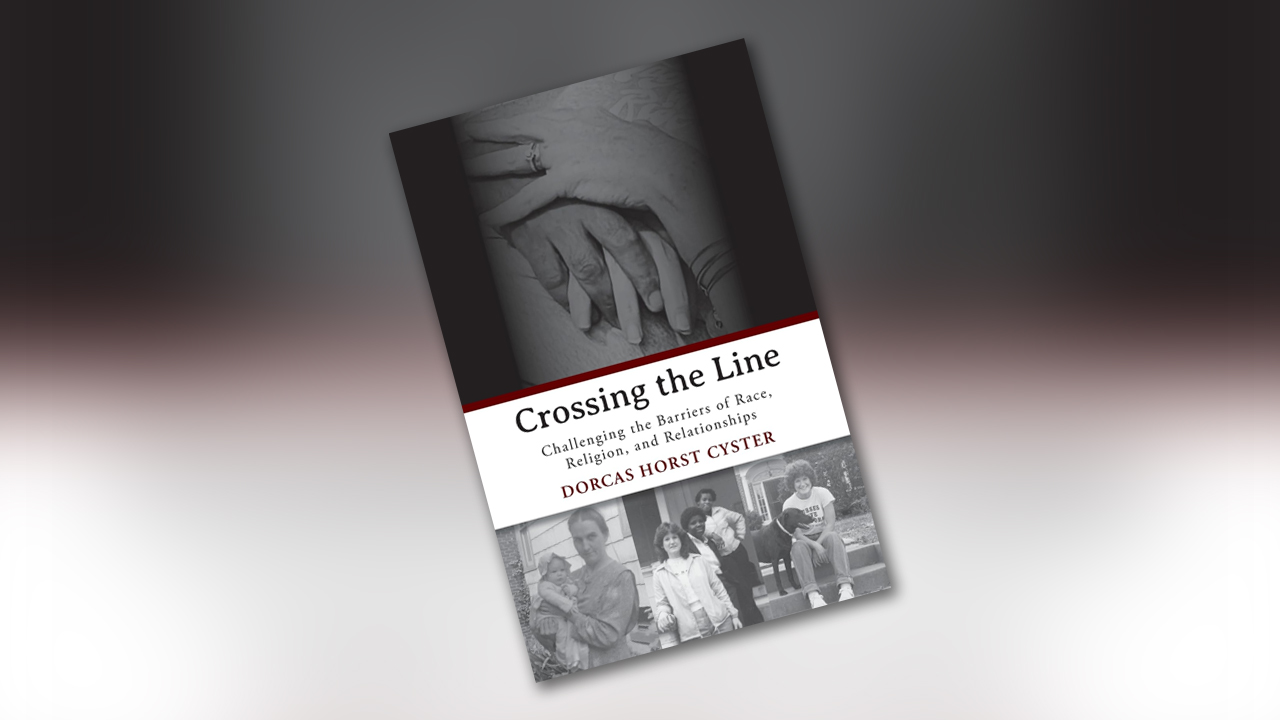

Rarely have a book’s final lines spoken so clearly to me and to the moment, when hate and rancor dominate our national discourse and cruelty seems the guiding principle of many national leaders. “I believe that love and kindness are organic to our souls,” Dorcas Horst Cyster writes in the epilogue to her memoir, Crossing the Line. “It is up to us to do whatever is necessary to roll back the cover of our fear and cross the line into the redemptive process of love.”

Cyster’s memoir testifies to the power of redemptive love. Born and raised in a conservative Mennonite family, she has stepped outside her privilege and into the lives of those from different cultural, racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. She crosses lines to build relationships, seeking the “common need for community and harmony” given by our Creator.

These efforts are not easy, nor was Cyster always accepted by the communities she has entered, especially after leaving her cloistered upbringing in Berks County, Pa. Her memoir starts there, in a childhood idyll of summers roaming a large, wooded property. But “there were deficits” in growing up Mennonite, including what she saw as Mennonites’ judgment of those considered “other.” She has “spent much of my life unlearning conditional love and embracing unconditional love from my God, my husband and many others who love freely.”

After receiving a certificate as a practical nurse, Cyster joined Mennonite Voluntary Service, traveling to Jackson, Miss., and living in a predominantly Black neighborhood. This was the first of many times Cyster would cross a racial line, developing friendships with Black neighbors, Black coworkers and Black church members.

After her MVS term, Cyster stayed in Jackson, attending a Voice of Calvary congregation, a multiracial church far different than the monolithic churches to which she’d been accustomed. But it was her decision to participate in “Reconciliation Meetings” at the behest of her brother-in-law that Cyster began to fully understand her White privilege. Her sister’s marriage to Spencer Perkins (son of the famed civil rights leader John Perkins), and his challenge to truly listen to young Black activists in their anger and grief at these meetings, was transformative for Cyster. She describes her recognition that “color blindness” was harmful and that God calls us all to do justice for those most affected by America’s tragic history. Her time in Jackson opened her up to friendships with people who changed her irrevocably.

This includes Graham Cyster, a South African she married in 1986. In the race classifications of apartheid, Graham is colored (mixed race). He had traveled to the United States, hoping to secure financing from Mennonites for a ministry in his homeland. The partnership he sought did not come to fruition, but he and Dorcas got engaged four months after they met. They faced discrimination because of their interracial relationship, both in the United States and then in South Africa.

The last part of Crossing the Line details the Cysters’ life in South Africa, including their creation in 1988 of The Broken Wall Community, a sanctuary for people oppressed by poverty and racialized violence. But those who lived on the 10-acre property also faced discrimination: To some, it seemed unfathomable that people of different races could live together in harmony.

The end of apartheid (at least officially) and the election of Nelson Mandela represented a shift in the BWC’s ministry, even as deep chasms continued to separate people in South Africa. Mandela’s victory caused jubilation, but it also meant shifting priorities. Donations began to wane, and with the BWC’s end the Cysters moved back to the United States in 1997, along with their two daughters.

She continued to cross lines, working for racial and socioeconomic justice as she raised her daughters, became a grandmother and earned her bachelor’s degree in nursing at age 60. She says the war of the powerful against the powerless is still a global one, and so she has sustained her work of advocating for the marginalized, attending pro-democracy protests and standing up against Moms for Liberty and other ultraconservative groups who have tried to reshape the public schools where her granddaughter attends.

Crossing the Line is not always a comfortable read. Cyster calls out those who create barriers to people’s thriving, including the Mennonite church as an institution, as well as other Christian organizations who focus on the afterlife without liberating people from oppression here and now. Her story reminds us that hope is found in redemptive love, when we set aside our fear and cross lines to reach others.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.