The Anabaptism celebrations held earlier this summer marked five centuries since a radical movement began. But I (Josh) was reminded that the Anabaptist story not only encompasses the past 500 years but continues moving forward, as my family and I spent the first half of August traveling through Málaga, Barcelona, Glasgow and Belfast in preparation for our return to cross-cultural ministry.

In many places, the next chapter is being written by people who, as my friend Hal liked to say, entered Anabaptism the old-fashioned way: by choice as adults — those bearing it as a conviction and who didn’t inherit the tradition. In places where lived faith and going to church are well outside the cultural norm, there are Anabaptist-inspired communities experimenting with practices that feel both ancient and surprisingly fresh.

Here are five lessons those of us rooted in the cultural Mennonite world may heed from these neo-Anabaptists.

1. Anabaptist practices translate well into post-Christendom contexts

As Christendom — the marriage of the Jesus movement to the values of empire — fades, small practices such as neighborly service, peacemaking, radical enemy love and hospitality carry credibility. These actions speak volumes louder than dogma, and people who normally have no interest in church definitely notice.

In each location we visited, the Anabaptist tradition was being studied and interpreted as a counterpoint to local nominal Christianity, spiritual poverty and imported evangelical fervor that means well but often doesn’t do the hard work of being incarnational and approaching relationships with mutuality.

Takeaway: Anniversaries celebrate the past; living, Jesus-centered communities determine the future.

2. Radical inclusion must be learned

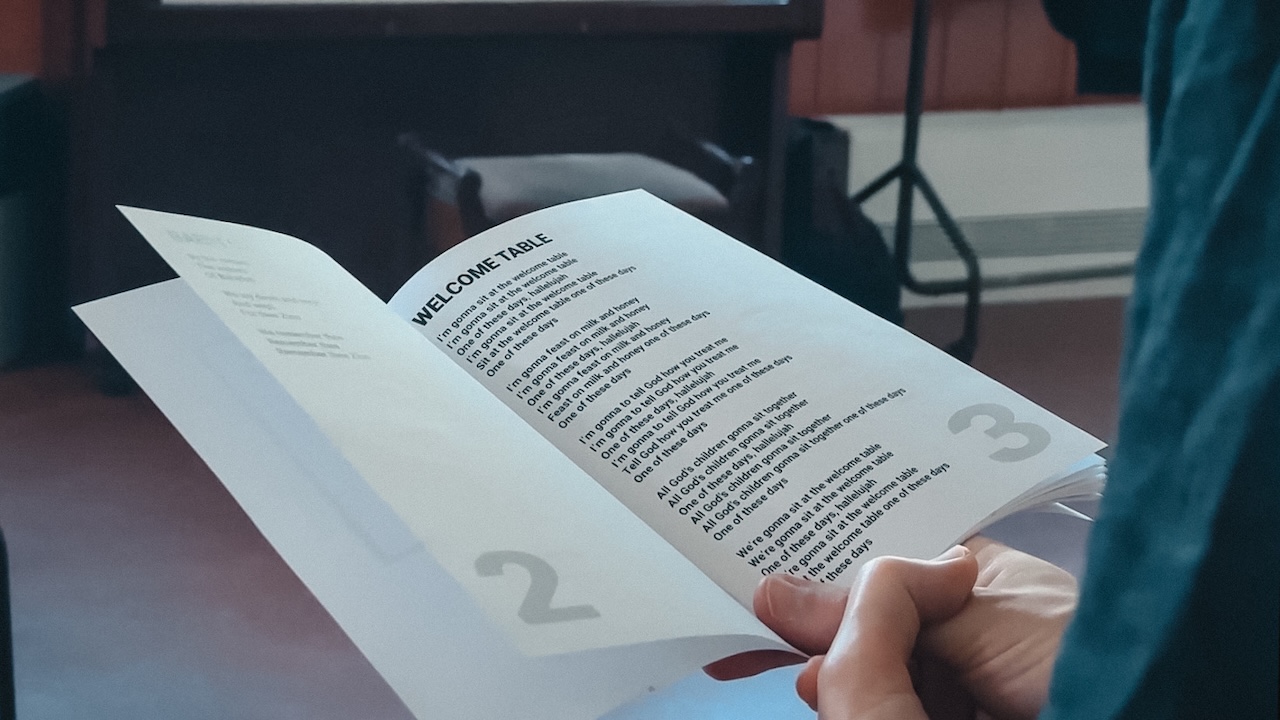

Across Belfast, Scotland and in the community we had served in Barcelona, we saw groups intentionally making space for people who don’t fit tidy categories. That welcome required repeated choices: changing liturgy, opting for the unpopular, tolerating (and celebrating) awkwardness, de-prioritizing comfort and confronting community gatekeepers.

Often, this posture was the result of a communal journey. And, despite the fear that adopting an inclusive, dynamic posture of welcoming all people will result in an exodus of community members, we’re seeing that is not necessarily the case. Fewer people left than anticipated and, while some did leave, these churches tend to be more unified, stronger and more mature. They’ve grown in number and in their capacity to meet the broken and marginalized castaways in their own communities. This is a noteworthy counterpoint to the argument that such textured conversations should be avoided in the name of preserving communal unity.

Takeaway: Extending the table is an acquired, vital discipline.

3. Outsiders often validate what we live

In Barcelona, we were given an unexpected glimpse into what happened to the church we’d been serving after we left. Part of the story involved an outsider who stepped into a pastoral role, listened to the way we lived and for what we advocated — shared leadership, steady hospitality, a posture of full inclusion — and said, “This is what we need.”

The result is a community that seems profoundly different from the one we knew, and that quick, plain affirmation carried more weight than any debate.

Takeaway: Affirmation may come when people beyond our circles name the value of our habits.

4. Shared life looks countercultural . . . and monastic.

In Glasgow, I met “Anabaptist Franciscans” who kept a steady rhythm of meals, service and prayer. “Shared life” isn’t just an ideal that takes place on Sundays and midweek life groups. It’s an integral part of a rhythm that forms patience, mutual accountability and a deep spirituality.

You can see an example of a newer embrace of monasticism we encountered in Urban Monastic. Although this group doesn’t identify as Anabaptist, it shares several Anabaptist principles and sometimes works in Anabaptist-leaning spaces.

Takeaway: Rhythm, intentionality and presence trump programming when it comes to building community.

5. Check actions before labels

Our European neo-Anabaptist friends were often puzzled by American groups that claim an Anabaptist label while espousing positions that run counter to historic Anabaptist commitments. With post-Christendom prompting a reevaluation and embrace of Anabaptist values for communities emerging from empire, Christian nationalism — a full-fledged declaration of loyalty to empire — is especially confounding.

It’s a reminder that a community reveals its true commitments more reliably by how it positions itself within society than by what it names itself.

Takeaway: Let witness be the measuring stick.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.