It is Wednesday, Jan. 21. My flight lands in Minneapolis just before midnight. Even fully protected, my hands and toes are freezing, but my heart is warm as I enter the eye of the storm.

As I arrive, Minneapolis is one of several U.S. cities occupied by federal immigration agents. It’s in the national media spotlight — a battleground between protesters and 3,000 federal agents, who outnumber local police by about five to one. The agents have already killed one U.S. citizen, Renée Good, 37.

Mennonites, along with other faith communities and residents, are caught up in these events — organizing vigils, mass meetings and collective witness as their neighborhoods are under attack.

This is the story of what I witnessed.

It is Thursday, Jan. 22. An urgent call has gone out for interdenominational faith leaders to gather for training and to participate in events led by the advocacy group Multifaith Antiracism, Change and Healing (MARCH). Over 700 people have registered.

A press conference was planned, but details of the location and time were hidden in secrecy and not given to me until a couple of hours before. I could already start to feel what was at stake.

At the press conference, faith leaders, led by Marianne Budde — the Washington bishop who pleaded with President Trump for “mercy on immigrants” during his inaugural ceremony — issued a statement outlining their demands for the immediate withdrawal of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, accountability for the killing of Renée Good and an end to federal funding and corporate cooperation with ICE.

A faith leader of Hispanic descent — whose name, like others quoted in this article, is withheld to avoid amplifying risk for local leaders — fiercely declared his local community’s motto, “I am brave because we are brave,” as a symbol of resistance during the ICE occupation.

An African American leader said: “Peace is the antithesis of violence, our tool against violent acts,” echoing the nonviolent message of Martin Luther King Jr. during the civil rights movement.

I was able to have a moment with Budde. “This is not happening just in Minnesota,” she told me. “It’s happening all across the country. This is a particularly intense and expansive operation of ICE. Seeing what’s happening here and what could happen everywhere, we must not leave one state alone but stand together. We have to be as supportive as we can and [offer] a common witness to what we aspire in our country.”

As we spoke, I could see the determination in her eyes. Despite her soft voice and unassuming presence, people lined up to speak with her — a brave leader who might guide us out of this moment.

I was also able to talk to another woman, a Protestant pastor of an LGBTQ-affirming community.

“When the united church is more like a movement, it is more faithful,” she said. “When it is more like an institution, it is less faithful. The best movements are rooted in love, not just what we are fighting against. Do something concrete as a witness to your faith.”

After the press conference, I drove back to the warm home of my Mennonite hosts. The Latina mother and her blue-eyed daughter, with many of her father’s features, described how their lives had changed over the past few months. An ICE neighborhood “prevention” packet, complete with a whistle, lay among the daughter’s toys.

The mother showed me a map on IceOut.org, where people report sightings of ICE agents.

I couldn’t help but feel the similarity to when Covid first hit, when people checked maps based on their location to see how many were affected. This time, the virus was ICE, and it was deadly.

She said they kept their doors locked and “check where people are reporting the presence of ICE and make sure nothing is happening near my house before leaving. I try not to go out by myself or drive in case our car gets stopped. There is no sense of freedom.”

Later that day, I volunteered to pick up the same woman from one of her daily routines. Aware of the risks, and following the advice of others, I carried my U.S. passport inside my winter jacket, pressed close to my chest, a precaution that became routine.

At the pickup location, I parked and waited. Moments later, an imposing SUV rolled slowly past in the opposite direction, carrying two White men. We made eye contact for a second before I looked away and then checked my rearview mirror.

The vehicle stopped. My heart skipped a beat. Assuming they were ICE agents on patrol, I silently prayed they would not turn around. After a moment, the SUV moved on. A minute later, the Latina woman I had come to pick up stepped out of the building and walked the 50 feet to my car, unaware of what had just unfolded.

Here we were, two immigrants with different legal statuses, driving home together. We arrived safely that day.

In the evening, there was an art build for signs ahead of the massive protest planned for the following day. The event was organized by a group led by high school students and a few college students. Their youth was a reminder of what was at stake — their futures.

One of the invited speakers, a Latino man, shared his experience of being held by ICE in a detention center for 13 months. With tears in his eyes, he told of leading a hunger strike with other detained immigrants, an act that contributed to the closure of detention centers in Georgia during the Covid era.

“When I came out of detention, I started joining forces with organizers outside, doing trainings and sharing my testimony,” he said. “My faith was big part of why I stood [up] to being oppressed. I was a light in the darkness. It was my responsibility to let that light shine.”

It is Friday, Jan. 23. A massive protest against the ICE occupation is taking place today downtown in Minneapolis. Earlier, I talked by phone with one of the Black leaders of MARCH, a priest whose voice echoed the moral clarity of Martin Luther King Jr.

“We are manifesting the presence of God in our bodies and our fate in a way that is the most vivid example where the Christian witness has stood up in a profound way,” he said. “When George Floyd was murdered, we were holding the understanding we had to do something, that something had to change. We were drawn closer together in different churches. . . . Peace churches need to articulate, very critically, the curse that the violence that is perpetrated upon us is doing.”

It is still morning. I receive another call asking if I can join a protest unfolding at that very moment at the airport. A group of clergy is gathering there to pray and bear witness in response to detentions and deportations. Time is rushed, and I am not able to go, but the call lingers with me as the day moves forward. A few hours later I learn that more than 100 clergy remain kneeling, praying and singing until they were eventually arrested by local police. All this happened before the mass protest. I was impressed to see the commitment to peace and justice by these leaders. It truly showed their character.

Preparing for the coldest day of the year in Minnesota, local Mennonites shared their winter gear: insulated overalls, ski goggles, hats, gloves. I felt as though I was heading to a battlefield. My gear consisted of a passport, recording equipment, extra batteries and a camera. Journalistic weapons. I would shoot photographs instead of bullets. Speak of nonviolence!

I drove toward one of the Mennonite churches, where people who were joining the protest would carpool downtown. About 30 people had gathered in the church basement as they sang and prayed. As I took out my camera, a member asked me not to take pictures, fearing that revealing their identities might put them at risk.

After the prayer, everyone gathered their “ammunition” — hand warmers, extra winter gear — and proceeded toward the protest. I was advised to keep my GPS location turned on so I could communicate with the people I carpooled with in case anything happened.

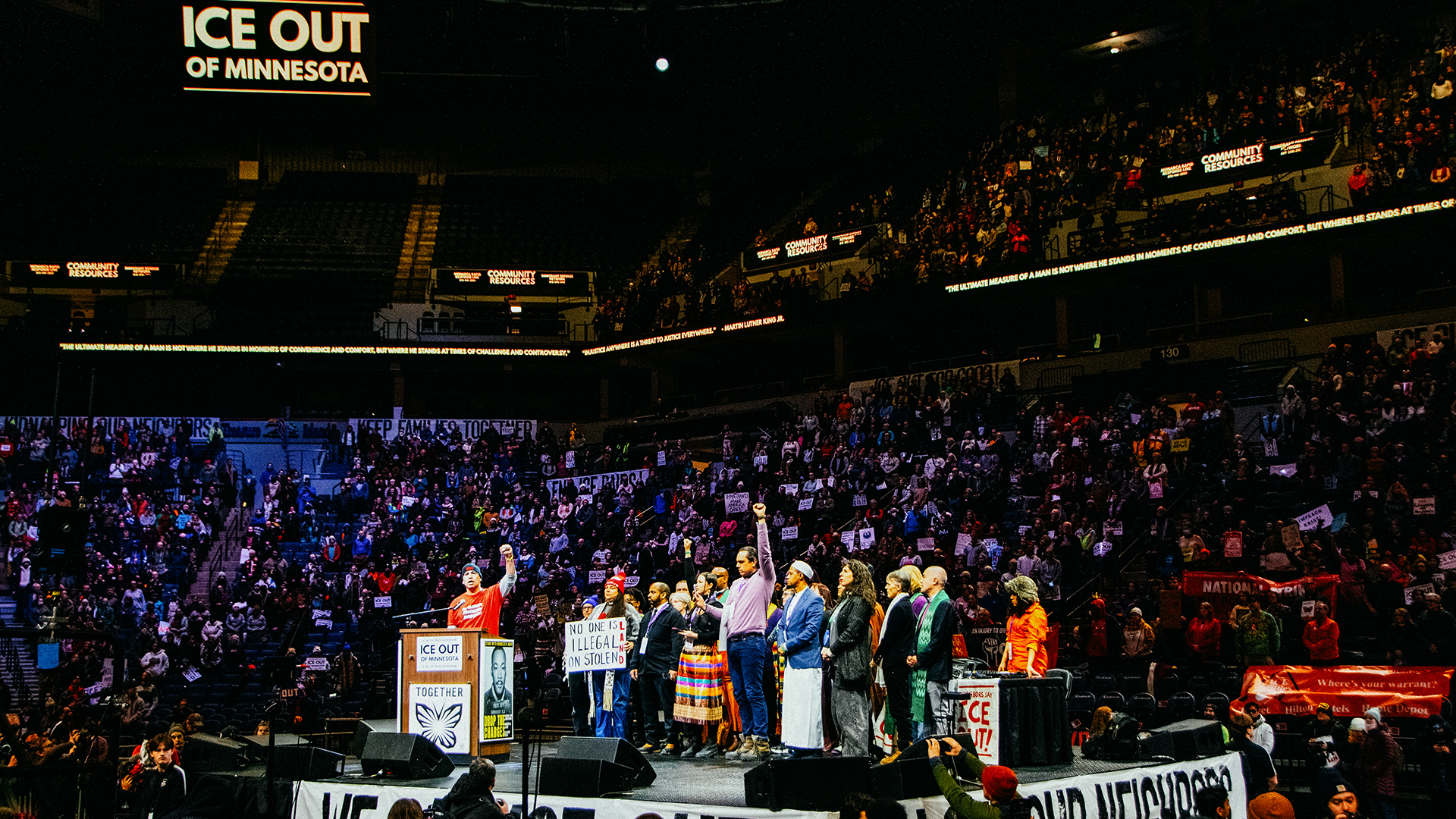

People had already gathered by the thousands. The moment felt symbolic and even biblical — a day of collective action triggered by outrage over the killing of Renée Good. People chanted, “ICE out of Minnesota!”

The protest would be a journey of at least a mile from downtown to the Target Center arena. Along the way, I could see people of all colors marching and holding signs, wearing ski masks, heavy winter clothing and colorful attire. They were channeling their anger by marching together peacefully. They represented the warmth of Minnesota: kind, loving people.

Somalis and members of other targeted immigrant communities offered food and hot drinks. Locals offered hand warmers (as if I didn’t have enough already!). With signs reading “Immigrants Are Welcome Here,” the march crossed a street featuring a giant mural of local artists Prince and Bob Dylan. Next to the painting was a quote from one of Dylan’s songs, “The times they are a-changing,” written more than 60 years ago and still as relevant today.

At the Target Center, we listened to musicians, messages from faith leaders and testimonies of immigrants — among them an Uber driver whose comedic face-to-face encounter with ICE and one of its public leaders, Greg Bovino, went viral on social media. Like the Uber driver, these are now our heroes: ordinary people leading a movement with dignity and peace.

The Mennonites told me there would be a church service that evening organized by a Black congregation. Faith leaders from various denominations would speak. I was excited to hear what they had to say.

I had never been to a Black church. The soulful music, choir and musicians brought joy and warmth. A gospel piece with the words, “After you’ve done all you can, stand up,” brought tears to people’s eyes.

It felt as if we were all speaking a common language, much like the protest earlier that day.

Throughout the “Prayer Service for Truth and Freedom,” everything focused on the historic moment and the shared message of “love thy neighbor.” This had become the standing ground of the movement against ICE repression — a new ground to defend, in order to survive.

Bishop Budde and the others echoed one another’s messages, weaving faith and action into every word. After the service ended, people from various denominations, Mennonites, protesters and others, hugged as if they had known each other for years.

It is Saturday, Jan. 24. I’ve managed to get a good night’s sleep and have several interviews lined up. The day will be busy and, so far, I feel hopeful.

The first Mennonites I met were a multiracial family — a Latino man and a white woman, both U.S. citizens. They welcomed me into their home, their children still in pajamas. We gathered in the kitchen, and they told me how their lives, too, had changed.

“I need to make sure I have my passport and an Airtag [GPS] that my wife knows I carry with me in case something happens, so they know how to find me,” the man said.

The woman said: “My husband doesn’t go out by himself for activities other than work. I take him or do the errands. I am constantly checking my phone to see his location. I worry about him being detained. There is a general sense of [being] on-edge, paranoia. Life is not the same. When we first got here, it was lovely. We loved seeing the diversity in Minnesota.”

The husband concluded: “We rely on our faith community, and it’s been incredible to not feel alone in this city. They have been very supportive toward our family.”

I arranged to meet in a coffee shop with a Mennonite leader who had been in the protest the day before. I appreciated that he made time for me amid his responsibilities as a community leader and a father. Time felt especially scarce and valuable — every second counted. Everyone that surrounded me had turned into activists — a reality I hadn’t fully considered before.

He ordered a coffee and a small chocolate chip cookie, and we began our conversation.

“In general, there is desire in our Mennonite community to be involved in social justice issues, to be involved with our neighbors, the call for justice and peace,” he said. “We seek to live out an alternative in our congregational life, but our witness is not limited to our congregational life. It also extends out to the streets.

“The Anabaptist movement started as a protest of the Christian nationalism of that era. You can see the parallel. They assumed a lot of cost, and we wonder, What does that look like in our time? . . .

“Nonviolence has to be active, a desire for justice and denouncing injustice. Our congregation is connected to the broader community in some civil disobedience. Some of us do quieter means of resistance — food drives, giving people rides, being on neighborhood control.”

Despite his relatively young age, I sensed this soft-spoken leader’s wisdom and maturity. At times he crossed his hands in a reflective way, almost as if preparing to pray. Our conversation lasted less than an hour, and I cherished every minute.

I met another community leader, a United Methodist clergy, who was also at the MARCH gathering.

“Literally any moment or any day, there could be an active abduction I come upon,” she said. “It’s an indescribable stress.

“As a deacon, my ordination calls me to call the church to the world for justice and compassion. That really shapes my world view. In this moment it feels particularly important. If we can’t show up in the face of this evil, we are not living into our vows.”

She kept glancing at her phone. She paused and said she had been called as part of a response team, something common now.

And the latest word was this: A young man had been killed by ICE agents. His name: Alex Pretti.

In that moment, all the effort of the day before — withstanding the harsh weather and standing with the community — felt as if it might have been in vain.

After our conversation, I went quickly back to where I was staying and decided, for my safety, not to do more interviews that day.

Or so I thought. But my phone kept ringing. People were reaching out, offering to be interviewed. I promised to protect their identities to avoid any possible risk.

A member of a local Mennonite church said: “Jesus spoke truth to power. Mennonites and Anabaptists, if you are following Jesus, you need to do the same. Nonviolence needs to be creative in this context to support our communities.”

Another said: “We can have the confidence of God’s ultimate victory and presence during trials and tribulations. This is the faith I’m following.”

Later that day, in the home where I was staying, there was a family celebration: After a long search, the Latina woman of the house had received a job offer she had hoped for. Joy amid chaos.

That evening, I talked to a Mennonite leader who invited me into his home, a space filled with art and music. A Bible rested on the coffee table, opened to the Psalms. He said his congregation had just read Psalm 139, in which the writer says he hates the wicked but concludes, “search me, God, and know me. Change anything in me that needs to be changed.”

“ I like scriptures that acknowledge the rage that comes from witnessing injustice. ”

The leader continued: “Christians have a story we put ourselves in that tells us where history will end up: the redemption of the world through the person of Jesus, who faced a Roman Empire. I think that is a helpful analog to think about: If we put ourselves in this story, we know that good prevails, which can involve a lot of sacrifice. . . .

“Nonviolence is really a symptom of love for people you hate. The act of loving somebody that you don’t want to love. That is really hard. ”

“Our church protests, does money offerings for immigrants who can’t go out to work and need help with their rent, does food banks. We pray for people, get training for what to expect when confronted by ICE. ”

“When stuff like this happens, it reinvigorates people’s involvement in community, and it can strengthen faith communities. We now have Christians and Muslims talking closely together.”

He concluded: “I know readers of AW might be all over the political spectrum, but if you were here and seeing how people are being treated — totally at odds with how we as followers of Jesus are called to treat other people, especially immigrants — you would stand up for them.”

I got a last-minute call from Mennonite community leaders saying they would host a vigil that night. And they had finally approved me to take pictures.

My hands couldn’t bear the cold for more than 10 minutes. I had to go inside the church to warm my hands and then go back out.

The congregants held a candlelight vigil for peace after the shooting of Alex Pretti and sang hymns. About 40 people stood outside the church and marched around the block. They sang, “This little light of mine, I’m going to let it shine.”

When I got to my bed, I wept. Earlier, I had felt hopeful, but this day had been different. The killing of Alex Pretti felt like a direct response from ICE to the protest the day before. We got the message: They would not hold back.

It is Sunday, Jan. 25. There’s a quiet, grim ambience in the neighborhood. People are not smiling. Local news media show neighborhoods in the area with empty open cars and broken windows. The cold bites the air.

I joined the thousands who gathered downtown in an emergency protest for Alex Pretti. The sun shone on the protesters as they chanted, “ICE out of Minnesota,” a refrain repeated from the days before.

I saw many signs — “It’s not the cold, it’s the inhumanity. Ice out!” — and one with a peace dove: “Act for justice, pray for peace.” A Mennonite man held that sign. I told him I was with Anabaptist World. We shook hands and began to march.

Soon I had another commitment — an interview with a Lutheran pastor, a Latino, who had been at the MARCH gathering and whose words had resonated with me: “I am brave because we are brave.”

When I got to the church, the pastor was running late. He was bringing boxes of tacos to a celebration for the birthday of an immigrant congregant. He showed me the temple with signs saying, “Aquí estamos y no nos vamos!” (Here we are, and we are not leaving!). A medium-sized dog that he always brought to church sat on his lap as we talked in his office.

“In the chaos our community is facing . . . [we] let faith guide us instead of fear,” he said. “These are the same people who are most vulnerable, and that takes courage, even when it means risking your life.”

He spoke of faithful solidarity — solidario — as a willingness to risk comfort and to insist that all people have access to their most basic needs. Drawing from his experience with Anabaptist communities, he emphasized that nonviolence is not passive but disciplined and costly.

“People are putting their lives on the line, using cameras and whistles against weapons,” he said. “That is how we are confronting evil.”

I asked about the Hispanic families in his congregation.

“Many are realizing the American dream they bought into is not real,” he said. “They came believing this place would protect them after escaping so much, and now they are wrestling with the fact that this reality exists here too.”

After I stopped recording, I wept. I couldn’t believe his resilience in the midst of what seemed like despair.

He comforted me with a few simple words: To confront this darkness, we should simply live and insist on joy, whether through music, dance or food, in hopes of changing the future.

As I left the church, SUVs drove around the block. Paranoia crept in again.

I had a couple more interviews with a Mennonite man and woman who told me about their roles as community leaders in neighborhood and school watches.

“I wake up earlier that I used to,” the woman said. “I open the Signal Chats [encrypted text message platform] and prepare myself for whether I am going to respond to something or start my normal work day.

“I attended a training by Mennonite Action some months ago — how to mobilize yourself to be prepared to act when things were scaling up in community as a group and as individuals. What is the moment you would be compelled to action?”

The man said: “After Renee Good was murdered, agents went to a high school and were wrestling students and detaining teachers, deploying pepper spray on school grounds. This mobilized parents to establish countermeasures to observe, watch and alert. During the school week there are probably five to 10 messages per day to respond in the school watch.”

The woman said trained observers tried to have “many observers on sight when there is a noted incident and make sure it’s documented — video, peacefully — in hopes that the ICE agents will use restrained force. [But] it doesn’t mean it will be like that. When this happens to a person alone at a public space — for example, a bus stop — the observers can at least capture the person’s name or a contact number. They can call to let someone close to them know they have been taken. The whistles are to make noise to alert people in the general area of the presence of ICE.”

On the brighter side, the man said: “I’ve gotten to know more of my community members and trust them. I talk to them daily and this gives me hope. I felt this call because this is not the world I want to live in. It is not right.”

The woman continued: “So much has been lost in terms of individuals’ power and autonomy. It feels that if I can’t speak now, it will be too late to change anything. . . . I don’t want to wait until they come for me, too. I want to be active on behalf of others.”

It is Monday, Jan. 26. My flight to return home was canceled because of winter storms, so I had to book another and get out of there as soon as possible. I couldn’t stand to stay in that reality much longer — a reality that, like Covid, has deeply changed people’s lives, with the presence of ICE agents increasing under a federal enforcement operation that has sparked unrest and tragedy in Minnesota. The stuff of nightmares.

The story is not over, but I have to stop, at least for now. Questions linger: Are we all going to live this same reality unfolding in cities across the United States, under repression like in Minneapolis? When life and liberty are at stake, what are you willing to do for your community?

Thoughts to ponder. A new day will come.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.