The news has been filled with stories of ICE raids and families living in fear of sudden abduction — children kept home from school, parents terrified. Reading those headlines, I couldn’t help but think of my mother — seven years old in post-war Germany — hidden in a shepherd’s hut when Soviet agents came looking for refugees to force back to Stalin’s brutal regime.

Different time, different continent, but the same terror: the knock on the door, the scramble to protect the vulnerable, the question of who will stand up and help.

In February 1945, Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt met at Yalta and agreed that post-war Germany would be divided into zones of occupation. In the same negotiations, Roosevelt and Churchill conceded to Stalin’s demand: all Soviet citizens found anywhere in Germany were to be repatriated — without consent and by force if necessary. When the war ended, Soviet agents moved freely through the Allied zones, searching for refugees — including German-speaking Mennonites who had fled Ukraine during the war. British and American troops, bound by Allied agreements, often provided logistical support. By autumn 1945, more than 2 million people had already been sent back — mostly in cattle cars to the north without clothing or food. Survival rates were grim.

For Mennonite families in the British Zone, daily life settled into a tense mixture of routine farm labor and constant fear. Soviet commissars held meetings in villages and towns known to have their former citizens, urging people to be ready when the trucks arrived. Refugees returning from the fields often feared they would find a Soviet vehicle waiting. Host families were often protective, but their ability to shield their guests was uncertain.

In Bonstorf on the Lüneburg Heath — where my mother, grandmother and aunt were placed — meetings with the commissars were held regularly. Attendance was mandatory for both hosts and refugees. Before one meeting, Hans Hilmer, who was hosting my grandmother and children, hid my mother and four other children in a shepherd’s hut on the heath. Windows shuttered, forest noises outside, danger just beyond thin wooden walls — she experienced much during the war, but never forgot that evening and the post-war fear. The Hilmers repeatedly offered to hide the family in their attic whenever Soviet trucks appeared. They understood the fear — and they acted.

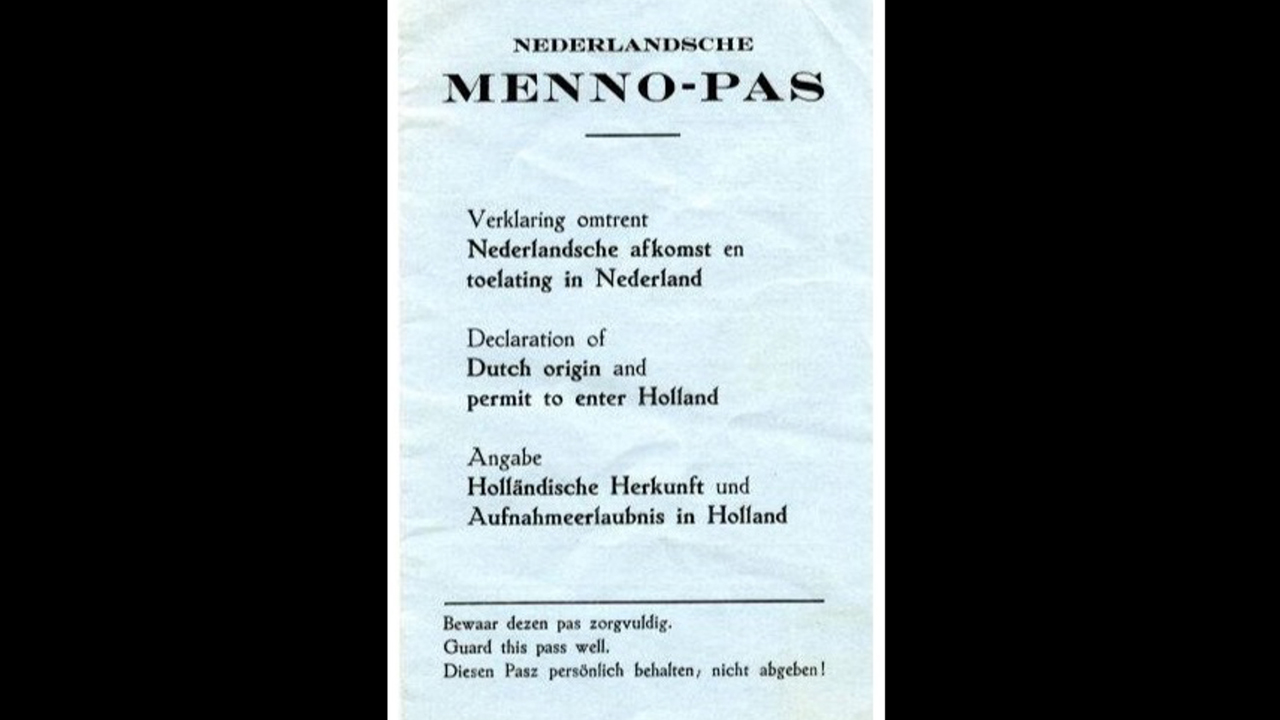

By early 1946, panic spread. Orders came to list all refugees who had been Soviet citizens prior to 1939. Behind the scenes, Mennonite Central Committee and Dutch Mennonites worked urgently to create escape routes. A single sheet of paper circulated quietly among refugee families: “In case of extreme danger…” It was a lifeline. Our family slipped away toward Holland, carrying little more than one suitcase each and hope. Of the 35,000 Mennonites resettled in Germany during the war years, only about 12,000 ultimately escaped Stalin’s claw-back.

History repeats in different forms. Today, vulnerable families still live with fear of being taken and sent to places of retribution where death is a very real possibility. There are creative things that can be done to protect the vulnerable: to hide them, to open a border, to provide alternate identification. Local German churches helped locate refugees. British pastors negotiated their protection. Dutch churches extended their identity to include people who had not been “Dutch” for 350 years. North American churches negotiated with occupation forces and the International Red Cross to name their own “commissar” with a pass and a jeep to move freely through all zones to find and collect “their people” — in competition with the Soviets doing the same.

The United States today is different. However, it has become a dangerous time for the vulnerable — and for those who seek to protect them. The nation that has so long been a beacon of liberty and democracy is shutting off the lights, one by one.

Maybe this story provides some inspiration and courage to our friends in the U.S. looking to stand in the gap. When the trucks came, the Hilmers didn’t look away. They opened their home, their attic, their hearts. That choice saved lives. May we choose the same.

Arnold Neufeldt-Fast is associate professor of theology and dean of the seminary at Tyndale University in Toronto and an ordained minister in Mennonite Church Eastern Canada.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.