What shape will our Anabaptist witness take in the next 500 years? What spiritual resources will carry us forward in a world of political polarization, technological acceleration and swelling violence?

A surprising conversation partner may help us ask these questions with new clarity: Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th-century philosopher best known for his critique of Christian morality.

Nietzsche was not a Christian, yet in The Antichrist he offers a provocative interpretation of Jesus’ nonresistance. He saw Jesus not as weak or passive but as a person whose inner freedom was so deep that retaliation became impossible.

This “spiritual strength that does not strike,” he believed, was the most radical thing Jesus embodied.

While Nietzsche rejected institutional Christianity, his description of Jesus unexpectedly echoes the earliest generations of Anabaptists — women and men who followed Christ’s peace not out of fear but conviction.

That resonance invites us to consider: How might a renewed Anabaptism draw from this deep well of nonresistance?

I offer four suggestions:

1 Understand nonresistance as a way of being.

Nietzsche argued that Jesus’ refusal to retaliate came from an inward transformation — an absence of resentment, fear and vengeance. The Sermon on the Mount was not a moral code but the expression of a new consciousness.

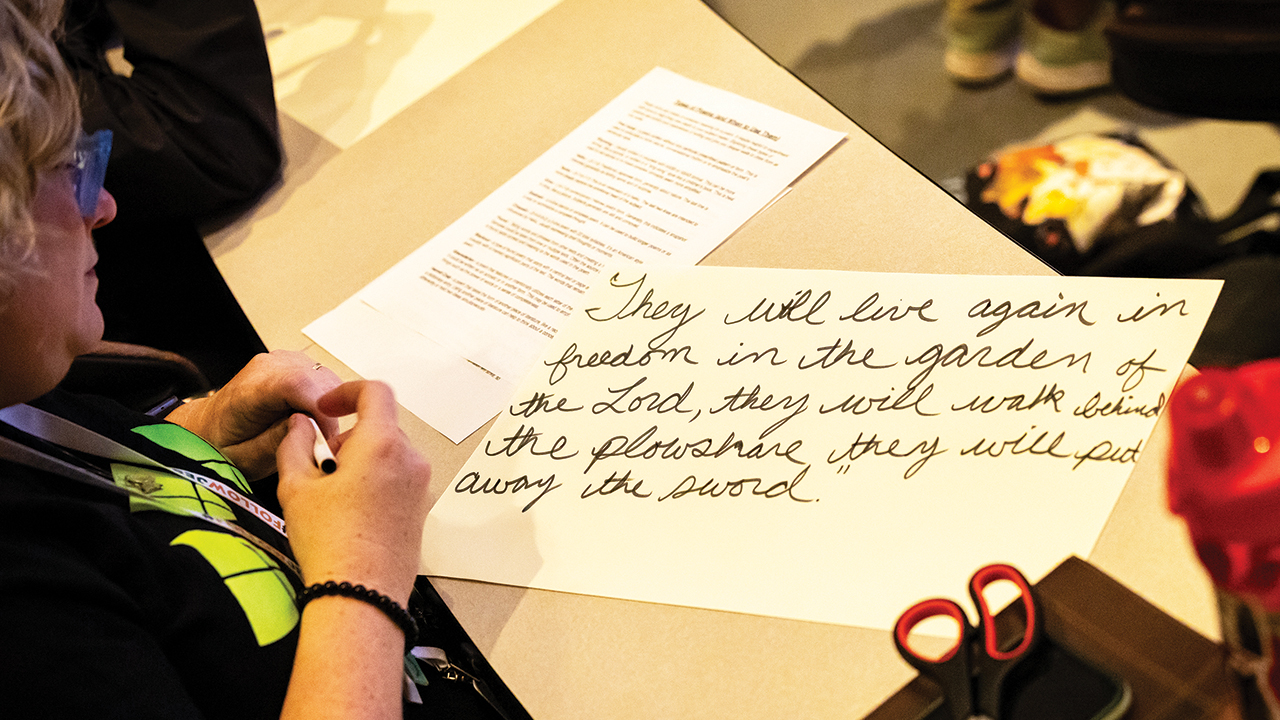

Early Anabaptists, though using different language, recognized the same truth. When they refused to fight, refused to retaliate, refused to swear oaths, it was because they saw violence as incompatible with the spirit of Christ. Their peace witness rose from a transformed heart, not a calculated political position. They lived a way of peace that welled up from inside.

If we imagine the future of Anabaptism, this seems essential: Nonresistance cannot survive as a slogan or a stance — “the peace stance,” as Mennonites have sometimes called it. It must be a formation of the inner life, a shaping of imagination, emotion and desire.

The church of the future will need Christians whose reflex is peace not because they are passive but because they are spiritually free.

2 Draw from a legacy of courage.

During the world wars of the 20th century, many Mennonite and Amish communities maintained this inner commitment to peace under enormous pressure. They endured prison sentences, ridicule and economic loss, not to win moral arguments but to remain faithful to Christ.

Their story suggests another truth for the decades ahead: Nonresistance will require courage, not comfort.

If the 21st century continues trending toward militarization, nationalism and fear-driven politics, a future Anabaptist witness may again look costly. Are we willing to become the kind of people who could make choices similar to those of our ancestors?

3 Make nonresistance active.

Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. demonstrated that nonresistance is not retreat. It is active, creative force. Their movements show what Anabaptists have always proclaimed: Refusing to strike does not mean refusing to act.

The Anabaptist future will need engaged peacemaking, where nonresistance expands beyond personal behavior and becomes a public, reconciling presence in:

— polarized communities;

— climate-scarred regions;

— prisons and detention centers;

— digital spaces;

— urban neighborhoods;

— rural towns wrestling with fear and despair.

Nonresistance must grow from not killing to actively nurturing life.

4 Root our faith in inner freedom.

If Nietzsche admired Jesus for anything, it was his inward freedom: a heart that could not be corrupted by resentment. Early Anabaptists would have named this same freedom the work of the Holy Spirit.

A faithful Anabaptism in the future, then, must cultivate:

— communities where fear does not rule;

— habits that free us from resentment;

— worship that trains us in compassion;

— practices that restore our imagination;

— disciplines that shape peace into instinct.

The world’s crises — ecological, political, racial, technological — will only intensify the temptation toward fear and retaliation. The future church must be formed in a peace stronger than the world’s anxiety.

What might Anabaptism look like in the next century? I hope it will be:

— a community of inner strength, not merely outer stances;

— a church of courage, willing to pay costly witness;

— a network of reconcilers, healing fractures others have abandoned;

— a people who refuse resentment in a time addicted to outrage;

— a quiet fire, burning with the Spirit’s peace.

I want to be part of a church that still believes the deepest truth our forebears lived: Peace is not weakness. It is the fierce, liberated life of Christ among us.

A life rooted in love and freed from fear is what the world now desperately needs. It may be our most powerful gift to the future.

Keith Lyndaker Schlabach and his brother Brent Lyndaker are the co-founders of PeaceGrooves (peacegrooves.com), an Anabaptist-centered arts and publishing collective committed to creative peacemaking.

Have a comment on this story? Write to the editors. Include your full name, city and state. Selected comments will be edited for publication in print or online.